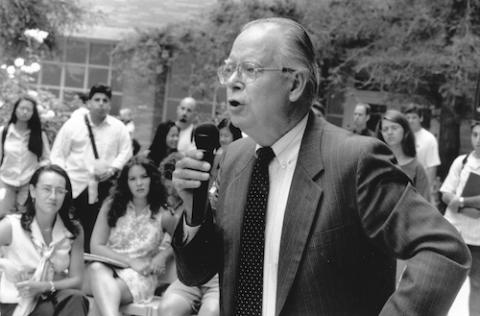

Cruz Reynoso: UCLA Law Remembers a Colleague and Legal Trailblazer

The loss of former California Supreme Court justice and UCLA School of Law Professor Cruz Reynoso, who died on May 7 at age 90, has left the UCLA Law community saddened.

Members fondly recall a formidable but thoroughly humble and kind collaborator and mentor who rose from a childhood as the son of migrant workers to become California’s first Latino Supreme Court justice and then a treasured UCLA Law professor for 10 years in the 1990s.

“Cruz Reynoso was beloved by generations of UCLA Law students who benefited from his extensive practice and judicial experience,” says Professor Laura E. Gómez, a close colleague. “He inspired Latino students and young lawyers by sharing his personal story – often punctuated with phrases and truisms in Spanish – as one of 11 children whose parents migrated from Mexico to rural Orange County, where he worked in the fields through high school.”

Reynoso’s time at UCLA Law came during the latter part of a trailblazing career that culminated in 2000, when President Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

After earning his B.A. from Pomona College and LL.B. from UC Berkeley School of Law, Reynoso worked in private practice in El Centro, California, and served on the California Fair Employment Practices Commission and in the California governor’s office. For two years, he was an attorney with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in Washington, D.C. He then returned in 1968 to direct California Rural Legal Assistance for four years before shifting to work in the judiciary and academia.

Reynoso taught at Imperial Valley College, Berkeley Law, UCLA Law, and the University of New Mexico School of Law. In 1976, Governor Jerry Brown appointed him to the California Court of Appeal.

He served there until 1982, when Governor Brown elevated him to the state’s highest court. Marked by his firm stances on the rights of non-English speakers and other civil rights matters, Reynoso’s tenure on the Supreme Court was relatively short-lived, as strong political opposition swept him and other liberal justices off the court in 1987. He returned to private practice before arriving at UCLA Law in 1991.

Teaching courses in remedies and professional responsibility, Reynoso bonded with students, who valued his mentorship as the faculty advisor of what were then named the Chicano/Latino Law Review, American Indian Law Students Association, and La Raza Law Students Association, plus moot court. In 1995, they elected him Professor of the Year.

“Students loved him,” says Distinguished Professor of Law Emeritus and Interim Dean Emeritus Stephen Yeazell. “He was patient, he carefully prepared, he spent hours and hours with them – if you were a student, you could be in Cruz’s office and he’d talk to you about remedies or life or whatever you wanted.”

Distinguished Research Professor Carole Goldberg remembers collaborating with Reynoso during the fraught period following the passage of Proposition 209, which ended affirmative action in California. That moment included his leadership of a 1997 “teach-in,” where UCLA Law community members shared their views on brewing admissions changes.

“Cruz and I co-chaired the challenging committee that was charged with fashioning a law school admissions policy,” she says. “Because he never vilified those with opposing views, he kept temperatures down and enabled discussion of contentious matters. However, his ever-kindly manner coexisted with an unwavering insistence on achieving racial justice. His personal experience as well as his history of advocating for marginalized communities gave him a moral authority that I, and so many others, admired and respected.”

Reynoso taught at the law school until 2001, when, after years of commuting to Southern California, he moved to UC Davis School of Law to live with his wife on their nearby ranch.

Even with his impressive record, Reynoso is, in the end, remembered for his steadfast collegiality. “I joined the UCLA Law faculty a few years after him,” Gómez recalls. “I was a newbie, and he was a former California Supreme Court justice, so I was in awe of him! Of course, he put me at ease immediately, and he became a lifetime mentor and friend.”

Reynoso “had a lot not to be humble about, but he had no airs, no pretenses, he never puffed himself up,” Yeazell says. He remembers one instance when Reynoso saw that the microwave in the faculty lounge had gone missing and, rather than demand that it be replaced immediately, he simply went to the store and bought a new one for his colleagues to share. “It’s a small gesture, but that’s the kind of person he was – one of the world’s real saints. He was a gentle man, a humble man, and just a wonderful human being.”

-

J.D. Critical Race Studies