Holding police accountable: A book Q&A with Professor Joanna Schwartz

For more than two decades, UCLA School of Law professor Joanna Schwartz has been a leading authority on civil rights, with a focus on police misconduct. In 2020, with the murder of George Floyd and the national reckoning that followed, her work was thrust into the national spotlight. Schwartz became a regular contributor to major media outlets and advisor for others who were interested in how law enforcement officers can be held responsible for their conduct – and why, even now, they often evade any major punishment for the most egregious actions.

“Crises of misconduct and accountability emerge periodically, usually in response to viral videos of beatings or killings, but police misconduct and the need for better accountability have been important issues for as long as we have had police,” Schwartz says.

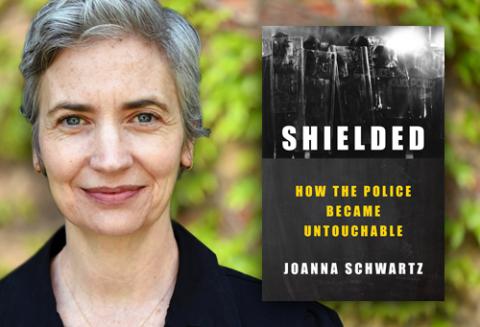

A former civil rights attorney, member of the UCLA Law faculty since 2006, and recipient of UCLA’s highest teaching honor in 2015, Schwartz has responded to the outcry with a new book, Shielded: How the Police Became Untouchable (Viking, 2023), that is filled with vivid stories illustrating the many ways in which the American legal system shields officers from accountability and prevents victims from receiving justice. As she makes clear, there is plenty to learn. “My goal is for readers to replace assumptions and anecdotes about how civil rights litigation works with information and evidence,” she says. Here, Schwartz talks about what went into her work on the book and some of its big lessons.

We hear the terms on the news all the time now, but what are qualified immunity and other constitutional or statutory shields for police?

Oh boy, there are so many. Qualified immunity is a legal protection that protects government officials — even when they have violated the Constitution — so long as they have not violated what the Supreme Court calls “clearly established law.” But, in Shielded, I argue that qualified immunity is only one of many protections for police: others include the way plaintiffs’ attorneys are compensated, which makes lawyers disinclined to bring civil rights cases; the detail plaintiffs must include in their complaints to get past a motion to dismiss; the Supreme Court’s Fourth Amendment doctrine, which is very deferential to the police; and the standards for holding local governments liable for misconduct by their officers.

The legal doctrines here are obviously complex, but how big of a problem is this? In other words, how many “bad cops” – and people seeking redress from them – are there?

We don’t have good data about how many “bad cops” or problematic forces or people seeking redress there are — in significant part because Congress doesn’t require police departments to gather or disclose any of this information. Departments don’t even have to disclose the most basic information about how many people officers kill each year. That, in itself, is a failure of accountability.

Looking at things more broadly, you have chosen to focus your career on civil rights law, first as a lawyer who spent substantial time practicing in places like Rikers Island, and now as a law professor. Why? And how did those early experiences lead into your work since?

I went to law school after working at an alternative-to-prison program in a criminal courthouse in the Bronx and thought that I was going to be a public defender. But after working in a prisoners’ rights clinic in law school, and working for a summer at a civil rights firm, I decided that I wanted to do work on the civil side, though still connected to the criminal justice system. I spent a handful of years working at a small civil rights firm in New York. While I was in practice, so much happened, and happened so fast, that I felt like I was drinking from a fire hydrant. My work left me overflowing with questions. Who is actually paying the settlements and judgments in the cases that we win? Where in cities’ budgets does this money come from? How does qualified immunity actually play out in most cases? Why is it harder to bring civil rights suits in some parts of the country than in others? These questions that kept me up at night while a young lawyer are the questions that I have tried to answer over the past 15 years as a law professor.

Another aspect of this issue that has arisen in recent years is how videos – from police body cameras or bystander videos – have helped shine a light on police misconduct. George Floyd’s murder under the knee of Minneapolis officer Derek Chauvin is, of course, a key instance. What has the impact of this technology had on courts and the ways that cases play out?

Videos have played an interesting role in civil rights litigation. In many instances, video has clearly corroborated one side’s version of events — making clear, for example, that a plaintiff did not resist arrest or throw the first punch. But videos do not always offer an accurate reflection of what happened, and research has also shown that people can view the same video in different ways.

Maybe that has something to do with where people come down on this politically fraught issue. What arguments do you find persuasive in support of the laws as they stand now, of offering police such a substantial and extraordinary legal protection?

The strongest arguments in favor of qualified immunity are predictions about how the world would be worse off without it — courts would be overflowing with meritless civil rights cases, officers would be threatened with bankruptcy every time they made a reasonable mistake, and no one would agree to be a police officer as a result, which would imperil our safety as a society. No evidence supports any of these predictions — and much of my research has shown that these predictions are exaggerated or just plain false. But I can understand why police officers and other government officials would be afraid of limiting or eliminating qualified immunity, given the horror stories that have been told about a world without that defense.

Your teaching at UCLA Law has also been rightfully celebrated over the years. How can law students best make an impact in this area?

Practice civil rights litigation or commit to take on some civil rights cases pro bono. Although there is a common assumption that there are many civil rights lawyers out there, the reality is that in many parts of the country a person whose rights have been violated will find it difficult or impossible to find a skilled civil rights lawyer willing to represent them. And once we have more skilled lawyers bringing these cases, they will not only make a difference for the clients that they represent — they can help improve civil rights doctrine for future cases.

In spite of all that we have discussed, the reality as it stands now is challenging. Efforts to reform the current legal standards regarding qualified immunity received more setbacks recently at the Supreme Court and elsewhere. So what’s next?

Those hopeful for police reforms have focused much of their attention on the federal government. Especially after George Floyd was murdered, there were hopes that the Supreme Court would limit or eliminate qualified immunity, or that Congress would pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which would have advanced a number of important reforms including the elimination of qualified immunity. The Supreme Court didn’t act and the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act failed after more than a year of negotiations. But there are a number of states that have taken up important police reform legislation, and some of the most ambitious changes have been enacted in Colorado, New Mexico, and New York City. States and local governments have proven themselves promising and creative laboratories of reform.

For more on Shielded and Professor Schwartz’s work, visit her website: www.joannaschwartz.net.

-

J.D. David J. Epstein Program in Public Interest Law & Policy