Intersectionality at 30: Q&A with Kimberlé Crenshaw

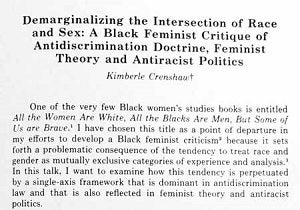

Writing from her office at UCLA School of Law in 1989, Distinguished Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw used the term “intersectionality” in a University of Chicago Legal Forum article to highlight the way that different forms of social inequality or disadvantage manifest and compound each other. The article, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” launched a concept that has since gained great traction in academia and popular discourse.

This year, Crenshaw participated in events that marked the 30th anniversary of intersectionality at the Gunda Werner Institute in Berlin, the Sorbonne in Paris and the London School of Economics. Gatherings are also scheduled at the American Studies Association and Columbia Law School. Crenshaw’s forthcoming book On Intersectionality: Essential Writings will be published in January. And the African American Policy Forum, which Crenshaw founded, recently launched a podcast titled Intersectionality Matters!

Here, Crenshaw discusses the evolution of her groundbreaking idea.

Entertainer Ariana Grande recently tweeted “it ain’t feminism if it ain’t intersectional” to her 66 million followers, and Hillary Clinton used the term during her 2016 campaign for president. How does it feel to see the term that you defined used so widely?

Surprising, many times exciting, sometimes puzzling and occasionally maddening. A reporter recently asked how it felt to coin a term that had become an overnight sensation. I told him 30 years was a pretty long night.

Has the idea strayed from your original intent or context?

Has the idea strayed from your original intent or context?

Ideas take on new meaning whenever they travel outside of their field of origin, so I can’t be surprised by some of the more curious articulations of the term. Commonly, intersectionality is framed as a synonym for diversity or identity politics. Both of those relate to intersectionality in some way, but neither is intersectionality per se. Less benign are claims that intersectionality sets forth a reverse hierarchy of oppression, creating a new class of pariahs among people who do not typically face intersecting forms of exclusion. Yet even these critics of intersectionality inadvertently seem to embrace the idea: Their grievance foregrounds the presumed impact of the concept on what many would call an intersectional group — straight white men.

It is not my view that intersectionality is any of these things. A counter-critique that I’ve framed as the antiintersectionality intersectionality during a couple of panel discussions I’ve organized in the U.S. and the U.K. is entitled “Myth-Busting Intersectionality.”

Please describe the conditions or people at UCLA Law that helped you to crystalize the idea of intersectionality.

Most significantly, UCLA hired me! I was young and untested when Professor Joel Handler brought me through, and I described the nascent project during my visit. “Demarginalizing” was my second article, but it was barely a draft when I joined the faculty here. School leaders at the time, Dean Susan Prager and Vice Dean Carole Goldberg, led a faculty that fully embraced scholarship that pushed the envelope, so although I knew I was writing against the grain, the signals within the building were encouraging. Indeed, the mentoring offered by colleagues here was more than I could have possibly expected. Some, like Rick Abel, Fran Olsen, Chris Littleton and others, provided a solid sounding board for me to further develop the argument. A small group of faculty here workshopped my drafts, and the wider assemblage of feminist law professors in California who met regularly also contributed to the sharpening of its argument. I also discovered a network of feminists of color, graduate students and young professors from several disciplines who also met on campus to support each others’ writing. Overall, my decision to come to UCLA is an important — perhaps even a “but for” — factor in the emergence of intersectionality in legal theory.

Twenty-five years later, you launched another phrase that has entered the cultural current, #Sayhername, to bring attention to black and female victims of police violence. What is the relationship between intersectionality and #Sayhername?

Twenty-five years later, you launched another phrase that has entered the cultural current, #Sayhername, to bring attention to black and female victims of police violence. What is the relationship between intersectionality and #Sayhername?

#SayHerName is an example of intersectionality in action, drawing attention to the way that police violence against Black women all too often falls between the cracks of anti-racist advocacy against abusive policing and feminist advocacy against gender-based violence.

Police violence is largely imagined to impact only men, and concerns about racial bias in police shootings typically focus on Black men. The reality is that girls as young as 8 and women as old as 93 have been killed by the police, and Black women are disproportionately vulnerable to police killings. But these facts remain largely irrelevant in the broader social debate because available frames are not capacious enough to address them. #SayHerName is part of a wider effort to address police violence against Black women so that the consequences of their vulnerability will no longer remain unmarked.

Political conditions and legal structures have changed quite a bit since 1989. Does intersectionality have greater relevance today than when you published your article?

Intersectionality retains its relevance today as its uptake by advocates and theorists continues to expand. Here in the U.S., the intersections of race and class continue to shape political and policy debates, even though they are often unmarked as such. Women of color are emerging as one of the most mobilized political constituencies, and many are gravitating toward agendas that are shaped by intersectional thinking. Intersectionality has been taken up outside the U.S., as well, particularly within the European Union, with its attempts to incorporate the concept into equality law, and in South Africa, where it has been referenced in the interpretation of the nation’s equality clause.

Intersectionality has become a pillar of Critical Race Theory, a discipline where you are among the leading scholars. In what directions do you see the field going?

Critical Race Theory has crossed over and seeded new projects across the academy. Critical Race Theory and intersectionality have been adapted in disciplines ranging from education, history, sociology and political theory to data science, public health, geography and environmental studies. I anticipate that these engagements will likely spur additional projects across the disciplines, like the one that was launched 10 years ago at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. Academics from multiple fields came together to examine how race has shaped the development of numerous disciplines only to be disavowed in the contemporary embrace of colorblindness. The project met a milestone this year with the publication of Seeing Race Again: Countering Colorblindness Across the Disciplines, a collection co-edited by Daniel Ho- Sang, Luke Harris, George Lipsitz and myself.