All Rise: The First 75 Years of UCLA Law

UCLA Law Magazine | Summer 2025 | Volume 47

UCLA School of Law opened its doors on September 19, 1949. But the law school’s story began a few years before its inaugural 54 students and six faculty members started classes in temporary barracks behind Royce Hall. California was a different place in the middle and late 1940s, with the centers of power and wealth only gradually shifting south. Los Angeles was brimming with promise, spurred by booms in movies and manufacturing and by the men and women who were migrating from the East or coming home from World War II. But those who dreamed of careers in the law and service had limited options, recalled William Rosenthal several decades after he had earned the nickname “the father of UCLA Law.” The city was home to only a handful of law schools, and all of them were private and therefore out of reach to many.

So Rosenthal, a member of the state assembly who represented the diverse Boyle Heights neighborhood, wrote up some legislation to create UCLA Law. The pushback was swift. A representative of UC Berkeley “told me I was too provincial and that we had no right to ask for a law school in Los Angeles County,” Rosenthal remembered. “And I told him, ‘We pay half the taxes, and we have half the population. I think it’s time that the poor kids would have a chance to go to a law school sponsored by the state.’” After years of effort, Rosenthal pushed the bill through. In 1947, Gov. Earl Warren signed it into law.

Rosenthal’s plan called for little more than an appropriation of $1 million. That was enough, he felt, to get the institution off the ground at the relatively new and spacious UCLA campus in Westwood. And it was enough to open access to a premier legal education and pathbreaking scholarship for decades to come. “I figured that was the most I’d be able to get,” he recalled with a laugh. “Let’s get enough for a tent … and then we can always add to it.

The million-dollar tent

UCLA Law has always been a big tent. In the 75 years since it opened in a city of excitement and energy, the law school has grown boundlessly. It has expanded generation by generation, while remaining firmly rooted in its original purpose — to be a place of opportunity, courage, and unwavering openness to new ideas, new colleagues, new ways of going about legal education, and new ways of uplifting students, causes, and communities around the world.

Through the years, well over 20,000 students have earned degrees at UCLA Law. Thousands more have served the community as members of the faculty and staff or as friends whose gifts have been immeasurable. Each one has shared that spirit of service and collegiality — and that instinctive drive toward excellence— that quickly came to characterize the new law school in the booming city several hundred miles south of San Francisco and Sacramento.

Dorothy Wright Nelson ’53 was one of the first people to carry that tradition. Years before she became a trailblazing law school dean and judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Nelson was one of the local kids whom Rosenthal had in mind. Born in San Pedro to a teacher and a building contractor, she earned her undergraduate degree at UCLA and entered the law school in its second class. There, she found guidance and grace when she struggled through the start of her legal studies — as well as a touchstone sense of fairness.

One mentor, she recalled, “said something that affected my whole career choice: ‘It doesn’t matter what the law is if the access to justice isn’t there. If the procedures keep people from having access to true justice, the system won’t work.’” She noted that she saw the sentiment repeated in the many clerks whom she hired from UCLA Law over the years. “That was embedded in my whole psyche at UCLA, and I’m very grateful.”

Even as UCLA Law’s ethos solidified during its first decade, the early years were marked by tumult under its inaugural dean, L. Dale Coffman, whose autocratic style led to a faculty revolt and his subsequent removal in 1958. That moment set a tenor that has characterized the law school ever since, recalled Norman Abrams, who joined the faculty in 1959 and later served as an interim dean of the law school and acting chancellor of UCLA. “Out of that period of turmoil, civility grew as a faculty value,” Abrams said. “A very strong sense of a shared community and getting along with one’s colleagues also became and have remained hallmarks of the school.”

Growth abounded through the leadership of the two deans who came next, Richard Maxwell and Murray Schwartz. Everything — from the number of people on the faculty to the number of volumes in the library to the reputation of the young institution — expanded.

“We became, within 10 years, a well-regarded law school, nationally well-regarded,” remembered the next dean, William Warren, who came to UCLA Law in 1959 after having departed the legal establishment in Illinois. “Opportunity here seemed greater than that anywhere else, and optimism was running over. And, I must say, I was swept up. … This is where the future is going to be.”

Renowned constitutional scholar Kenneth Karst was similarly pleased when he traveled from Ohio to join the faculty in 1965. “There are people here who provide a kind of … spiritual or emotional support, who want you to do well at what you do and want to help in any way they can, and they convey that by their manner,” Karst said. “We’re very lucky. … There is a sense of community around here that is very warming and enriching.”

Students felt it, too. Steve Lachs ’63 — who would later become the first openly gay judge in the world— was boosted by UCLA Law’s vibrancy and robust collection of people who made connections and got things done. It was, he said, “a dynamic and growing school. You could feel it. This was not a school that was just going to be sitting there. It was moving. And it was a good feeling to be a part of that.”

“Optimism was running over. And, I must say, I was swept up. … This is where the future is going to be.”

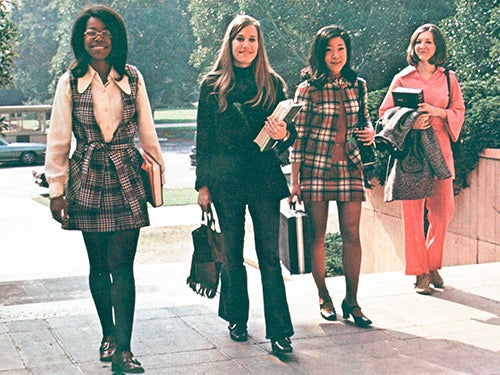

Emboldened by this steadfast commitment to progress, members of the UCLA Law community adapted notably faster to the times, when the broader society was gripped by radical change, than their counterparts at other institutions. The idea of rebellious lawyering in the public interest, of shaking up the standards that had bound legal education for far too long, took hold. UCLA Law was early in hiring women and people of color as professors. In 1966, the law school introduced the Legal Education Opportunity Program (LEOP) to bring in large numbers of students from underrepresented groups. The National Black Law Journal launched in 1970.

“UCLA Law had developed a reputation for inclusiveness,” remembered Carole Goldberg, who joined the faculty in 1972, a few years after the law school hired Barbara Brudno as its first woman professor. “When three females, including me, all agreed to accept UCLA’s offer, we were the talk of legal education. No major law school at the time had more than one woman on the faculty, if that. As the years passed, all three of us”— Goldberg, Susan Westerberg Prager ’71, and Alison Grey Anderson— “became tenured professors.”

Goldberg went on to enjoy a groundbreaking career as an administrator and one of the nation’s most prominent scholars of Native American law. “I have benefited from the law school’s empowering receptivity to new ideas and new areas of teaching and research,” she said. “To this day, my field of study has not been incorporated into the curriculum of many major American law schools. But because of UCLA Law’s deeply engrained spirit of innovation, I received a positive response whenever I developed new programs.” That positive spirit reverberates for alumni as well, long after they leave Westwood.

“Being at UCLA Law helped build the foundation for my career as a civil rights lawyer and law professor,” said Janai Nelson ’96, who, as the president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF), is the top civil rights attorney in the country. Through UCLA Law, she first externed with LDF and made invaluable connections with her Black professors, colleagues on several journals, and fellow members of the Black Law Students Association. “It’s hard to imagine surviving law school without those friendships and supports. The racial and ethnic diversity of the student body was one of the law school’s greatest strengths.”

After she graduated from UCLA Law, Antonia Hernández ’74 also embarked on an inspiring career of impactful service, including as the longtime head of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and the California Community Foundation. “UCLA Law, in many ways, through individual professors and deans, has tried very, very hard to really set itself aside and say, ‘We’re an L.A.-based institution, and we want to reflect the diversity of the place we’re in,’” she said. “I have to give them credit for that. I think that’s one of the reasons I have stayed connected and involved, because I do see the effort. I see them understanding it.”

Open for innovation, open to the world

Melville Nimmer was a respected lawyer when he joined the UCLA Law faculty in 1962. A year later, he published the first parts of his seminal treatise, Nimmer on Copyright, which remains the key practical guide on one of the most significant areas of the law — and quite possibly the most enduring work of scholarship ever to be born at the law school.

Three decades later, Ken Ziffren ’65, who studied as a law student with Nimmer, wrote about the insight and foresight that caused Nimmer’s celebrated work — which presaged issues in forms of media that had yet to be fully conceived — to come to life at UCLA Law. “He challenged befuddled students, academics, practitioners, and judges as no one had before,” Ziffren wrote.

It was a fitting summary of a culture of innovation that naturally sprang from the law school’s essential openness— a style that certainly inspired Ziffren, who pivoted from initial work in tax law to a pioneering career as an entertainment law luminary. He and other alumni would go on to help establish UCLA Law as the country’s top school for entertainment law. And, like so many successful graduates, he would give back in countless ways over the years, among them teaching and mentoring students and founding the Ziffren Institute for Media, Entertainment, Technology and Sports Law.

Not content to rest easy in the comfort of their community, other people from across the law school have branched out to meet the moment— in education, in scholarship, in contending with society’s biggest challenges, and in connecting with their colleagues around the globe.

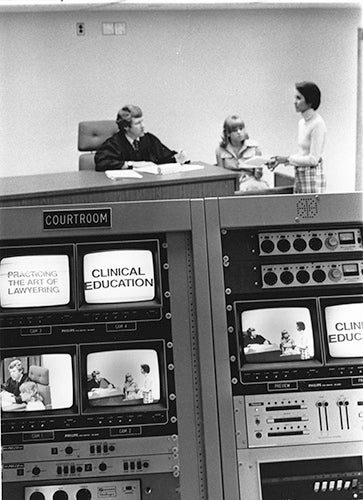

Starting in the early 1970s, that meant the launch of the law school’s pathbreaking clinical education program, which seizes opportunities to help real-world clients while teaching practical lawyering. “A lot of people went to law school in order to change society for the better,” remembered Paul Bergman, who co-founded the program. “They wanted an opportunity to do that while they were in law school. But what differentiated UCLA Law was that we primarily wanted to train lawyers not in legal analysis but in using legal skills, which the law school curriculum otherwise basically ignored. It was all about principles and reasoning and argumentation. But how do you work with clients?”

That global perspective— the kind of work that is done with an eye on places far beyond the classroom or California— has endured.

“A very strong sense of a shared community and getting along with one’s colleagues also became and have remained hallmarks of the school.”

In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw used the term “intersectionality” in an article titled “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” It remains a landmark work of scholarship and is a stark example of the profound ways in which the UCLA Law community came together to grapple with one of the most pressing issues.

And it is something that Crenshaw, a national leader in civil rights law and co-founder of the trailblazing Critical Race Studies program, said could really have only happened at UCLA Law. “‘Demarginalizing’ was my second article, but it was barely a draft when I joined the faculty,” she said. The faculty “fully embraced scholarship that pushed the envelope, so although I knew I was writing against the grain, the signals within the building were encouraging. Indeed, the mentoring offered by colleagues here was more than I could have possibly expected. Overall, my decision to come to UCLA is an important— perhaps even a ‘but for’— factor in the emergence of intersectionality in legal theory.”

But for UCLA Law

But for UCLA Law, researchers at the Williams Institute would not have had their work undergird the Supreme Court’s opinion on marriage equality. But for UCLA Law, students and staff with the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment would not have contributed to legislation that combats the devastation of climate change. But for UCLA Law, members of the Lowell Milken Institute for Business Law and Policy would not be producing impactful work on corporate law, bankruptcy, taxation, and more. But for UCLA Law, the people of The Promise Institute for Human Rights would not be on the front lines of the fight for human rights in places far from home.

And but for UCLA Law, new generations of students— J.D., LL.M., M.L.S., and S.J.D. alike — would not receive a legal education that is geared, quite simply and quite explicitly, toward improving lives.

Ariane Nevin LL.M. ’15 came to UCLA Law on a Health and Human Rights Fellowship after receiving her law degree in South Africa. Looking to become a more effective social justice practitioner, she scanned public interest programs at American law schools and landed on UCLA Law, where she recognized the names of several faculty members and instantly got excited by the idea of studying with them as an LL.M. student.

“I was completely blown away,” she marveled when she looked back on her experience and how it enhanced her work for prisoners and others in South Africa. “UCLA Law definitely affected the way that I practice. It’s given me a much more sensitive approach to advocacy, and it boosted my confidence. Coming back to practice [in Africa] with UCLA Law behind me makes me a more confident, stronger advocate.”

Ever strengthening. Ever evolving. Ever rising. At UCLA Law, for the 75 years that we celebrate today and for the 75 years to come: All rise.

“Our legacy and our future are one and the same,” said Michael Waterstone, the 10th and current dean of the law school. “We embrace visionary scholars, we educate and empower the brightest students, and we excel in carrying out our greatest tradition: creating bold new approaches to solving problems. I can’t wait to see what the next 75 years have in store.”

Read more in the 75th Anniversary edition of the UCLA Law magazine.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.