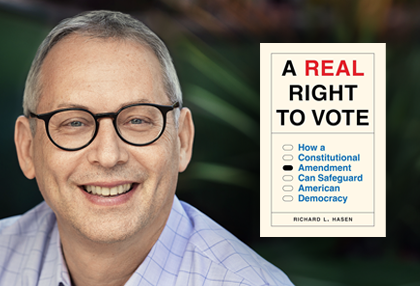

‘The best way to protect voting rights’: A book Q&A with Richard Hasen

As the director of the Safeguarding Democracy Project at UCLA School of Law and a frequent commentator in the media, Professor Richard Hasen is the nation’s go-to authority on election law. Now, with the fraught 2024 election campaign underway, Hasen is zeroed in on spelling out the stakes.

“Every election season, this country struggles with questions over whether we can have fair and safe elections,” he says. “That’s not how it is in other mature democracies. And so I started thinking about what is at the root of the problem. I became convinced that the best way to protect voting rights, lower uncertainty and the amount of election litigation, and protect against potential election subversion is changing the Constitution to provide an affirmative right to vote.”

That argument forms the core of his new book, A Real Right to Vote: How a Constitutional Amendment Can Safeguard American Democracy (Princeton University Press), in which Hasen breaks down the illuminating stories and history – social, legal and political – that brought the country to this moment. Hasen outlined his proposal in a recent article that he wrote for The New York Times, and he talks in this Q&A about why the matter is so urgent.

At the risk of sounding un-American, why is guaranteeing the right to vote important?

As I describe in A Real Right to Vote, historically there have been two different conceptions of the purpose of voting. One is to pick the “best” candidates or make the best decisions on ballot measures. That kind of thinking could allow limits on the franchise, like literacy tests or property tax requirements, out of thinking that this confines voting to those most “qualified” to make decisions. The other conception is that voting is about the division of power among political equals. In that conception, limits on who gets to vote violate basic principles of political equality. I argue that the second conception better reflects the ideals of today’s America, contained as far back as the Declaration of Independence, and that efforts to limit democracy by calling us a “republic” don’t really lessen the case for a political equality ideal of voting.

Why is there no affirmative right to vote in the Constitution? That’s surprising!

When the U.S. Constitution came into effect in 1789, it did not guarantee a right to vote for senators or the president – votes for those offices then were cast mostly by state legislatures. The founders were not keen on universal voting, so the Constitution allowed states to set the rules for which persons could vote in elections for the House of Representatives. Over time, the Constitution was amended to protect voting rights from discrimination, such as on grounds of race or gender. But it has never guaranteed the right to vote. Later court cases in the 1960s expanded voting rights somewhat, through a broad reading of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. People know a bit about the end result of those cases, like the “one person, one vote” rule, and assume that this is somehow written in the Constitution itself.

But why didn’t the drafters of the five amendments concerning voting seize the opportunity to enshrine a universal right to vote in the Constitution?

Voting is, of course, contested, and there is always a fear on behalf of those in power who would have to pass a constitutional amendment that expanding voting rights could lessen the chances of reelection and staying in power. It has taken social and political movements to move voting rights forward, and those have been the product of compromise. An early version of the Fifteenth Amendment would have come close to an affirmative right to vote, but it was rejected for fear that it would enfranchise too many people.

What did you discover in assembling the book’s vivid vignettes – like the story of Sgt. Herbert Carrington, who appealed to the Supreme Court for the right to vote as a military enlistee living in Texas in 1965 – to illustrate the history of major voting rights cases?

The Court’s track record is not good. In 1874, the Supreme Court rejected a claim by a Missouri woman, Virginia Minor, that she had the right to vote for president that Missouri denied to her because she was a woman. She claimed that voting was a privilege of citizenship protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. Later, in 1903, the Supreme Court said there was nothing it could do to protect the voting rights of Jackson Giles, who was denied the right to vote in Alabama because he was Black. The Court said that even after the post-Civil War passage of the Fifteenth Amendment barring racial discrimination in voting, it could not help. That sadly demonstrates that the Court has mostly been a laggard, not a leader, on voting rights.

You carefully elucidate the voting challenges that women and various populations – including Black, transgender and Native American people – have faced, but who would benefit most from an amendment guaranteeing the right to vote?

I think all of the American people would benefit. First, if we have a system where all eligible voters and only eligible voters can easily cast a vote that can be fairly and accurately counted, that’s good for both voting access and election integrity. And as Republicans make inroads in appealing to working-class voters, making voting more protected can help Republicans as well as Democrats. And we all have an interest in preventing stolen elections. Once we can get people to give up their misconceptions about voting, a voting rights amendment can be a win-win, not a zero-sum issue.

Given widespread fears about the misuse of governmental powers, how would a voting rights amendment prevent officials from flouting election laws, including the amendment itself?

The specifics of the amendment I propose would stop attempted election subversion in a few ways. It would guarantee in each state that the state’s choice of electors for president would depend on a popular vote and could not be taken away or interfered with by a state legislature. It would also provide a way for people to sue if there is a concern about election officials manipulating voting or voting technology. Of course, laws — and even constitutional amendments — can only constrain those who are committed to following the law. So an amendment is no panacea, but it would make stealing elections much harder.

How, then, would this amendment read?

In the book, I recognize that there are certain questions that are especially contentious in this already contentious area, like voting rights for former felons and the question of eliminating the Electoral College. For this reason, in the appendix, you can find both the “basic” amendment, which has six provisions, and then potential add-ons, to potentially address these especially contentious issues. I leave it to future political leaders to decide on the precise format of the amendment. The basic amendment’s six provisions are: (1) guarantee of the right to vote for citizen, adult-resident, non-felons, including in presidential elections; (2) equal weighing of votes; (3) automatic voter registration or national voter I.D.; (4) equal and non-burdensome voting opportunities; (5) protection of minority voting rights; and (6) broad congressional power to protect rights.

In one compelling passage, you discuss how the women’s suffrage movement steadily built over decades before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920. But how could the push for a voting rights amendment — which, you argue, we really need today, but which might not get enacted for generations — have an immediate impact?

Right. It took decades after the 1874 Supreme Court opinion in Minor v. Happersett, rejecting women’s voting rights, for the country to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. After Minor, a political movement grew in the states to expand women’s voting rights. By the time of the Nineteenth Amendment, 30 states had enshrined that right in state constitutions. We should learn this lesson and organize a similar movement to push for fair voting rights. It will pay dividends along the way, as state voting rights improve on the path toward a constitutional amendment. Of course, passing an amendment, especially in this polarized political environment, would be especially hard. But we think too small about political reform in this country, and things are not going to get better until we can get some more fundamental change.

What can law students do to make this ambitious proposal a reality?

The future is in the hands of today’s students. Don’t make the mistakes of the past by thinking too small. Now is the time to think about how to assure a fairer democracy and a brighter future for all.

In the end, what surprised you as you researched and wrote this book?

While I was not surprised about the lack of an affirmative right to vote in the Constitution like many of my readers will be, I was surprised at how poor a job the Supreme Court did over time in protecting voting rights. There’s really less than a decade of truly voter-protective decisions out of 235 years of the U.S. Supreme Court’s deciding of cases. It convinced me more than ever that we cannot count on the courts to protect our rights — we need to step up ourselves.

Join Hasen for a conversation about his book with Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of UC Berkeley Law, on February 15th at 7:30 p.m. at the Hammer Museum.