Celebrating Rand Schrader ’73: Gay Rights Trailblazer and UCLA Law Graduate

Visitors to the 6500 block of Hollywood Blvd. find themselves surrounded by monuments to Los Angeles greatness. There are Walk of Fame stars for Frank Sinatra and Orson Welles. The building on the corner bears a massive mural featuring generations of Lakers legends. And above the intersection, a street sign recognizes another L.A. icon. It reads: “Schrader Bl.”

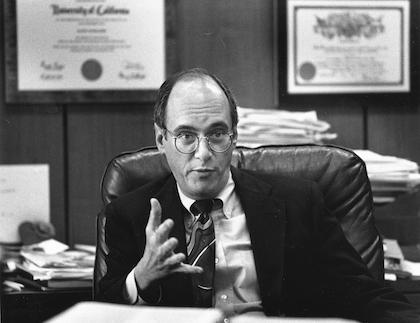

That sign, and the two-block stretch of sidewalk and pavement between Sunset Blvd. and Hollywood Blvd. that it marks, pay homage to UCLA School of Law graduate Rand Schrader ’73. His exceptional life as an attorney, judge, and gay rights activist is now fondly recalled through Los Angeles landmarks and the memories of those who knew him.

Schrader – an L.A. native who died of AIDS at age 48 in 1993 – was by all accounts brilliant, brave, kind, and deeply engaged. When he joined the office of the L.A. City Attorney in the mid-1970s, Schrader became the first openly gay prosecutor in the city and, quite likely, the country. His later appointment to the L.A. Municipal Court made him one of a few openly gay judges in the world – a trail originally blazed by his longtime friend and fellow UCLA Law alumnus Stephen Lachs ’63.

Schrader, however, had always risen above the risks of being an openly gay man in a still largely intolerant professional world. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times shortly before his death, he spoke of the challenges. “I went to the dean of the law school at UCLA and asked him: ‘Will I be admitted to the bar if I’m openly gay?’” Schrader recalled. “That’s how frightened we were.”

The hiring of openly gay lawyers in high-profile positions “just didn’t happen every day,” Lachs says. He and Schrader remained close friends through years of service on the court and in a tight-knit group dedicated to community activism, including as members of what is now the Los Angeles LGBT Center – which resides at 1625 Schrader Blvd. “When Randy got out of law school and ended up in the city attorney’s office, all of us in this little circle of friends were thrilled. It was a very exciting time.”

Burt Pines was the city attorney who hired Schrader. It was a transformative move that helped modernize and diversify the office, but, at the time, the decision to bring on an openly gay lawyer carried plenty of perils. “The city attorney’s office was not a welcoming place in the past,” says Pines, who ran the department from 1973 to 1981 and later served as a judge on the L.A. Superior Court. Pines’ initial election signaled change for a workplace that was almost completely filled with straight white male prosecutors who worked in tandem with a police force that was notorious for its raids on gay bars and bath houses.

“I knew that Rand was going to be watched,” Pines continues. “We had a conversation about that. I told him that I was going to hire him, but it was risky, and he had to be careful because he should assume that the police would be attentive to what he was doing. As a trailblazer, there was a lot of pressure on him.”

Fortunately, trouble never materialized, in part, Pines believes, because Schrader was such an impressive attorney: “Rand was hardworking, a team player, friendly, a good advocate for the prosecution in trials, and an excellent writer. He later became chief of our appellate section.”

At the same time, Schrader’s combination of daring and excellence inspired many. “One of the long-term deputy city attorneys came to me and thanked me for hiring him,” Pines says. “He told me that it was the first time that he had any real interactions with a gay man, the first time he ever worked with a gay individual, and it really opened his eyes. It changed his perceptions. Rand also opened the door for more gay and lesbian lawyers to apply, because they saw that this was a welcoming place. He had a profound influence on the office. It was monumental.”

Gov. Jerry Brown appointed Schrader to the bench in 1980, and he served with distinction until shortly before his death. All the while, he continued to practice the sort of understated activism and leading by example that had set him apart as a pathbreaking young prosecutor.

During his decade-plus as a judge, Schrader often promoted the success of gay law students. He was a leader of groups including the Municipal Elections Committee of Los Angeles, or MECLA, an early major gay political action committee. He went public with his diagnosis while serving on the court to show that people with AIDS could remain active and accomplished. And he helped found the main Los Angeles County facility for HIV care, which was renamed the Rand Schrader Health and Research Clinic.

Today, that center stands as one legacy commemorating Schrader’s incredible life. Another lives online: In a 1988 video that was posted by the foundation of Schrader’s longtime partner, philanthropist David Bohnett, Schrader speaks with trademark eloquence.

“Aren’t we good enough? Haven’t we suffered enough? Are gay people, men and women, not as worthy of self-respect and power as others?” he asks in honoring the lives of friends who had died of AIDS. “There is only one memorial worthy of [all those] lost to this disease, and that is to go forward with courage and spirit, to claim the ultimate victory of human freedom.”

Read more about Schrader in this profile of Stephen Lachs.