Pioneer, Presiding: Lachs ’63, World’s First Openly Gay Judge, Reflects

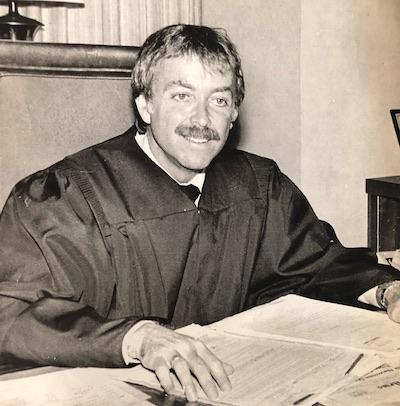

Within days of his appointment to the Los Angeles County Superior Court in 1979, a landmark event that made him the first openly gay judge in the world, UCLA School of Law alumnus Stephen Lachs ’63 could tell that things would never be the same.

“There wasn’t much question about it,” he says today. “I immediately started getting mail, literally hundreds and hundreds of letters from people all over the world. They would write to ‘Judge Stephen Lachs, Los Angeles Superior Court, Los Angeles, California,’ and it would all get to me. Most of the letters were congratulatory. A number of people wrote to me saying, ‘I can’t tell you how grateful I am for what you’ve done because it has inspired me. I never thought that I, as a gay person, could do anything, and now I see that you can do something with your life.’ I got so many letters like that. Even now, I could just about cry thinking about it.”

Lachs went on to serve with distinction, presiding over high-profile family law and other cases before he retired from the bench in 1999. Now 81, he works as a private mediator, and, in spite of his remarkable career, to this day considers himself, simply, “Stevie from Brooklyn.”

For him, that rise to the bench and sudden emergence as an inspiring figure of historic importance is an improbable story that involves hard work, determined activism, plenty of luck, and the life lessons that he learned in Westwood. For his alma mater, Lachs is someone whose humble leadership, immense success, and everyday heroism represents a style of excellence that has characterized UCLA Law students and alumni of all backgrounds since the beginning.

“UCLA changed my life, completely,” says Lachs, a Double Bruin who earned his undergraduate degree in political science. “It was the most important institution in my life, and I am eternally grateful for everything that was given to me there.”

‘They Want to Meet a Gay Lawyer’

Like many in the UCLA Law community, Lachs was not a Los Angeles native, but he quickly found a lifelong home when his family moved from New York City in the mid-1950s and he opted to attend the university and law school that were in his new backyard. The second member of his large family to attend college and the first to earn an advanced degree, Lachs adored law school, notably courses on securities transactions and income taxation. In the early 1960s, UCLA Law was barely a decade old and had yet to develop the vast networks of affinity groups, community outreach endeavors, specialized centers of scholarship, and experiential options that it is known for today. Still, Lachs says, “It was a dynamic and growing school, you could feel it. This was not a school that was just going to be sitting there. It was moving. And it was a good feeling to be a part of that.”

For more than a decade following his 1963 graduation, he worked at the California Department of Insurance, in general-practice law firm jobs, and for the L.A. public defender. In times that were far more socially unforgiving and professionally conservative, Lachs did not discuss his sexuality in public. He was not out beyond a small circle of friends – or, as he says, “out-out” – until the early 1970s, when an acquaintance asked him to attend a small meeting of gay law students who traveled from as far away as San Diego. Lachs remembers, “He said, ‘Would you like to come? They want to meet a gay lawyer.’ None of them had ever seen one before.”

So began his leadership in the burgeoning gay rights movement and community support groups. That included service on the board of what is now the Los Angeles LGBT Center and, years later, as a member and chair of AIDS Project Los Angeles. His legal career also blossomed following his representation of peaceful Vietnam War student protesters. In 1975, he took an exam and was one of three people selected from an applicant pool of 150 to become a superior court commissioner, an official who hears cases like a judge if the parties stipulate.

The end of the decade also saw a gradual shift in the shape of the legal profession and judiciary. President Jimmy Carter appointed a number of pathbreaking women and others to the federal bench. California Gov. Jerry Brown, then in his first two-term stint as the state’s chief executive, was elected with substantial support from members of the gay and lesbian community. They encouraged him to diversify the courts with one of their own, and Lachs, by then a respected commissioner with a decade in public service, was a compelling choice.

“As the song goes, The times, they were a-changin’,” Lachs says. “It was thrilling, I’ve got to tell you, living through those times, from the late-Sixties until the AIDS crisis. It was a thrilling, thrilling time to see the changes that were happening, in this country and, honestly, in the world. And to be a part of it? Oh my God.”

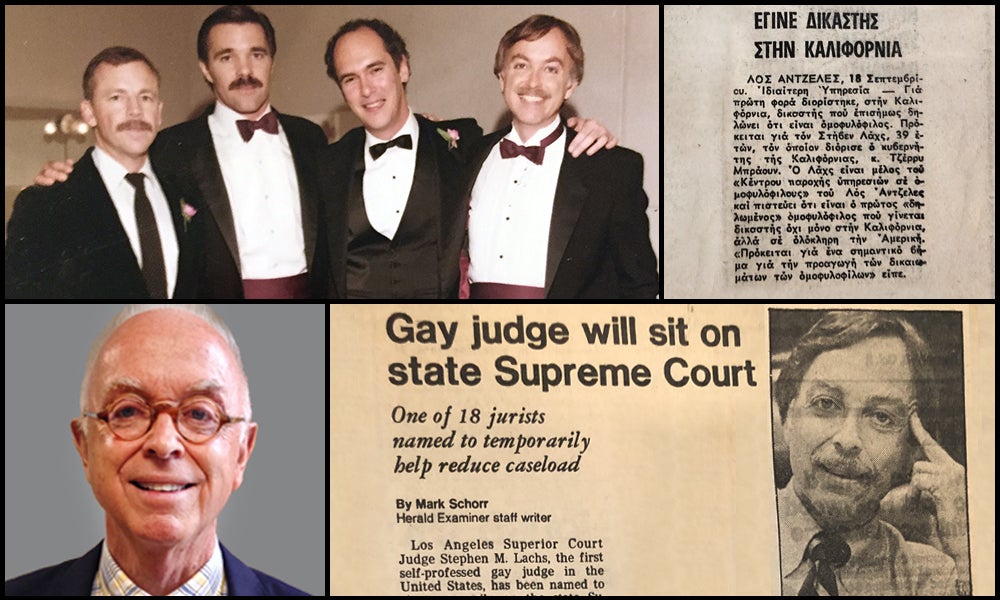

Lachs made global headlines when he was appointed around his 40th birthday. (While many sources establish that Lachs was the first openly gay judge in America, no evidence apparently refutes the presumption that he was also the first openly gay judge in the world, and Lachs has never heard otherwise. He admits that the ancient Greeks may have had judges who were out, but he adds that he is not a scholar of ancient Greece.) He was one in a small handful of openly gay government officials in the country. In a sign of the times, a headline and the caption on a widely distributed wire-service photograph called him “California’s first avowed homosexual judge,” a phrase that still startles. He had never expected to be such a trailblazer, he says, lightly adding, “I had barely taken my vows – as an avowed homosexual!”

But the world noticed. In addition to the flood of letters and newspaper clippings, Lachs was invited to speak at colleges and law schools around the country – at one event, he met Michael Ruvo, his husband of 41 years – and his connection to significant members of his community of advocates and attorneys strengthened.

Among them was Rand Schrader, another pioneering UCLA Law alumnus who had been the first openly gay staffer in the L.A. City Attorney’s office and would himself be appointed by Brown to the state municipal court in 1980. Six years apart in age, Lachs and Schrader had in fact met at that early-1970s gathering of gay law students, when Lachs came out. Schrader was one of the students. They remained close through the following two decades, loyal confidantes and colleagues in service and advocacy, until Schrader died of AIDS in 1993, at age 48.

A short time before, L.A. County’s main center for the care of people with HIV, which Schrader helped found, was renamed the Rand Schrader Health and Research Clinic. It remains today, among other prominent celebrations of his life. “He deserved it, he inspired a lot of people, and if you do that, you deserve those accolades,” Lachs says.

“But I knew him differently,” he continues. “We were both on the board of the [Los Angeles LGBT] Center, and I knew him as a friend – as a dear, close friend, not as a city attorney or whatever. For some of us, he will always be ‘Randy.’ He will always be an important, loving person. He was a vital friend of mine. I was so fortunate to have met so many wonderful people, and he really was one of them.”

‘I Wear My UCLA Cap’

Even in the early spring or late fall, temperatures can soar well into the triple digits around the home where Lachs and Ruvo now live in the California desert. Before the pandemic, they had been dividing their time between that arid resort community and their place in New York. But the past year has kept them on the West Coast and been one of slower days where all outdoor activities need to end before 10 a.m., when the sun gets too high in the sky.

Each morning, Lachs takes his little 18-year-old dog for a walk to a neighborhood park. Before heading out, he checks the newspaper’s sports section to find out about the latest Bruins victory, and he looks at the Daily Journal, which, he notes, is increasingly filled with retirement announcements for judges who had not yet joined the bench when he was on it.

Even if his decades of service had never made headlines, his record of accomplishments and dedication to the law – 20 years as a judge, 21 years and counting as a mediator, and nearly 60 years as a member of the state bar – would rise high above the norm. The multitude of cases still spark his mind. The poor families whose costly divorces he helped resolve. The ultra-wealthy businesspeople whom he navigated through the thorny thickets of who gets to use the private jet. And the two separate matters involving Michael Jackson, among countless celebrities whose problems, he firmly states, are just like everyone else’s.

It’s a history that Lachs is still living as he and his dog head out into the heat.

“It’s always sunny out,” he says, “so I wear my UCLA cap. Seriously. Without law school and the excitement that I felt and the enjoyment that I got from it, I never would have gone into law. UCLA is always going to be a part of me – a big part.”

Read more about Lachs in this profile of Rand Schrader.