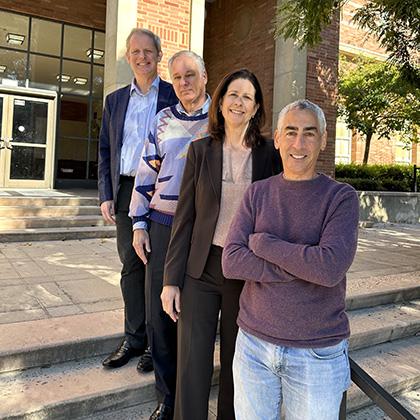

Four UCLA Law professors clerked for the late Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. They gathered to talk about it.

When retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor died in December 2023, the nation bid farewell to a historic jurist and figure in American government.

For four members of the UCLA School of Law faculty, her loss was especially personal: Iman Anabtawi, Stuart Banner, Daniel Bussel and Eugene Volokh had all served as clerks for O’Connor on the Supreme Court. Bussel, Anabtawi and Banner clerked for O’Connor after they graduated from Stanford Law School, while Volokh did so after earning his J.D. at UCLA Law. (UCLA Law’s O’Connor connections hardly end there. Three other UCLA Law grads also clerked for O’Connor: Sandra Segal Ikuta, Kevin Kelly and Brian Hoffstadt. And Kathleen Smalley, a lecturer at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management who has taught at UCLA Law, also was an O’Connor clerk.)

Recently, the four UCLA Law professors gathered for an informal roundtable discussion about their former boss. During the 90-minute conversation, they talked about working with O’Connor and being mentored by her, their views of her historic place as the first woman Supreme Court justice and their impressions of her legacy as a civic-minded public servant who broke ground throughout her life. Here are extensive excerpts from their exchange.

‘Extended family’

The professors began by talking about O’Connor’s funeral in Washington, D.C., which several of them attended, and reminiscing about their personal relationship with her.

Volokh: Every few years, when I was visiting D.C., I would come by and say hello. She also held yearly reunions for her clerks, and we got to see her.

Banner: My story is exactly the same. If we were in D.C., we’d see if she was going to be there and stop by, especially if we were with our kids. She always loved meeting her clerks’ kids, whom she called her “grandclerks.”

Anabtawi: I think she did think of the clerks as extended family. She always made time to see us if we were in the area and we contacted her.

Bussel: I was certainly respectful of her time and her position, but I viewed her as a mentor. I would interact with her pretty regularly, and I asked her for favors at different points. You know, my niece was doing a report, and she interviewed Justice O’Connor. She was in sixth grade or something, and that was very meaningful for me and my family. So I think that Iman is exactly correct: She treated her law clerks as a kind of extended family.

Anabtawi: She did connect with people, including her colleagues on the Court, intellectually and at a human level, in a very personal way. That’s one of the reasons she was so well-liked across the board by the other justices, and so influential.

Volokh: It’s funny you bring that up. She would invite her clerks who weren’t going home for Thanksgiving to have Thanksgiving with her. My year, it was at least two of us – and Justice Souter! I think she thought, He doesn’t have a wife and kids at home that he’d be going back to visit, so come to my house!

‘I’m at the Supreme Court!

All four had previously clerked for prominent U.S. Court of Appeals judges. At the Supreme Court, Bussel clerked for O’Connor during the 1986-87 term, Anabtawi in 1990-91, Banner in 1991-92 and Volokh in 1993-94 – times that, one could sense, felt like long ago … and like yesterday.

Banner: I remember showing up at the Court for my interview with Justice O’Connor thinking, Holy s---, I’m at the Supreme Court! [Everyone laughs]

Bussel: The custom in my era was that you applied to all nine justices, and the understanding was that the first one who extended you an offer, you would accept it and withdraw your applications from the others.

Volokh: Right.

Banner: And the chance of getting the job is so tiny that it would be a silly strategy to aim for any particular justice.

Bussel: That said, I was very pleased that it happened that Justice O’Connor was the first one that interviewed me and extended the offer, and I ended up working for her. When I was clerking, it was sort of the beginning of the golden age of being an O’Connor clerk. Scalia had just come on the Court, Rehnquist had just become chief justice, she had been on the Court five years, and she was no longer the junior justice. She was comfortable in the job, she knew the job. But her background was not as a federal judge, so she was still formulating how she thought about a huge range of issues. And so, we worked incredibly hard. I mean, we were talking about her in this sort of soft, kind of motherly family role, but as a boss, she was brutal! We worked from 8 a.m. until midnight, every day.

Anabtawi: We didn’t.

Bussel: We did. My era was a different time.

Volokh: It was a different time from when I was there.

Bussel: We got in at 8 a.m. when they turned the computers on. There were four of us. We had the flood of certs coming in that you had to keep up on. You had, out of 180 cases, 20 majority opinions, or more, would be assigned to O’Connor. So that’s five majority opinions for each clerk. And she was the center of the Court, so she was constantly writing separately! So, we had a huge workload. We were there from, literally, 8 a.m. to midnight.

Banner: Wow, that’s amazing. We did not.

Bussel: You know, they’d turn the computers off, you’d go home and get a few hours sleep, and you’d be back the next morning.

Banner: Well, she worked very hard herself, too.

Bussel: Again, it may have changed over time, but she was really still formulating her jurisprudence when I was working for her. She was trying to decide what she thought about various things, and she valued the interchange. It was a very heady experience, because you were with this very powerful person who was likely to have a decisive role in the resolution of what were the most controversial, difficult, important legal issues of that moment in time. I mean, now, 30 years later, there’s other things that are more important than whatever happened in October Term 1986. But at the time, it all seemed important.

Anabtawi: One of the reasons that we had so much work – Dan having had even more work – was that she really felt empowered when she was prepared. She was incredibly diligent. When we finished discussing cases, she would often just close the door and spend time in her office with a library cart and go over the primary sources, the briefs, the bench memos. I think that also gave her influence. She felt that she would be more influential if she were more prepared. She never was unprepared. And that led her to ask lots of questions, and that involved follow-up work for us. She was more effective as a result.

‘She was very conscious of her historic role’

O’Connor was the first woman to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court. From her appointment in 1981 until the arrival of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993, she was the only woman justice.

Volokh: My term was the first year that Justice Ginsburg was there. And she was thrilled that Justice Ginsburg came onto the court. That’s my understanding.

Anabtawi: Ginsburg, when she was a judge on the D.C. Circuit, was a major admirer of Justice O’Connor. When I clerked on the D.C. Circuit, my office was closer to Judge Ginsburg’s chambers than to my judge’s chambers. So I saw quite a bit of Judge Ginsburg. I did aerobics with her on occasion. [Everyone laughs] When she knew that I was going to clerk for Justice O’Connor, I remember her asking me about it, and it was so clear how much admiration she had for her. But going back to when I was clerking for Justice O’Connor, I think it really mattered to her that she held her own. I think that it weighed on her, and she most likely over prepared and went even further in being diligent than she needed to.

Banner: Do you think this was because she was conscious of her role as the first woman on the court? She didn’t want to let everybody down.

Bussel: Absolutely. She was very conscious of her historic role. It did not escape her that she was the first one. And she felt that pressure throughout her career. She was one of the first women at Stanford Law School, probably the first woman to be the majority leader of the Arizona senate.

Volokh: Yes, she was. Or of any state senate.

Banner: She actually talked about this once with us. She said that she knew that when she was appointed, There were probably thousands of people in the United States who are convinced that they can do a better job than I can. And she said, But you can’t worry about that. All you can do is just put your nose down and do the best you can.

Volokh: The sense that she wanted to be really prepared and really good at what she did, I think that was very much a part of her.

Anabtawi: She did; she set a high bar for herself. I think that it was very personal to her and extended to all aspects of her life. So, I do remember hearing that when she first went out to play golf, she didn’t tell anyone that she was taking lessons. And by the time she went out, she told people it was her first time on a course, and she didn’t do so badly.

Banner: Did any of you play tennis with her?

Anabtawi: I did.

Banner: Boy, she was competitive!

Bussel: She was super competitive.

Banner: I mean, she could get mad if you lost a point, if you played on her side in doubles.

Anabtawi: I thought that was just me! [Everyone laughs]

Bussel: But she’d instill that in absolutely everything she did. You know, if she went fly fishing, she was going to catch the biggest fish, the most fish! [Everyone laughs] She excelled in everything. She was athletic, she was brilliant, she had an enormous wealth of talents.

‘The swing vote’

Over time, O’Connor’s Western pragmatic conservatism placed her at the center of an increasingly polarized Court. She was deemed “America’s most powerful jurist,” and obituaries looked back on the later part of her tenure as the era of “the O’Connor Court.”

Volokh: I think it was just the accident of being the swing vote. If your views are somewhat less predictable, people will pay more attention to you, because that’s where the suspense is.

Bussel: Her role evolved into being the decisive center of the Court on a bunch of issues. In my year, Justice Powell was still on the court, and he was viewed as the center. O’Connor was viewed as a conservative in that era. But as the court evolved and its personnel changed, O’Connor became the center. I don’t know that she changed her views, particularly. I mean, the Supreme Court is sort of in an ongoing discussion with the rest of the country. The Supreme Court makes a decision, and then the society reacts, the state legislatures react to that, the congress reacts to that, there’s more litigation brought, the lower courts react, and the issues don’t go away, they just come back in different forms. She was very conscious of that process, and that was why she kept the decisions narrow. She was inviting that discussion. She had this intuitive connection with society. I think this is something we are missing now.

Banner: She is the last justice who had been an elected official.

Bussel: She had a unique background. She was raised on a ranch in the middle of nowhere, and all of the rest of it. But somehow, she had this intuitive connection with the society. And if you had something important, Justice O’Connor was the person you wanted to decide it.

Anabtawi: That’s a very fair point. She wanted to decide the concrete cases correctly. She also thought about the broader implications of the opinions that she was participating in deciding, including the language that was used and the policy implications of the decisions.

‘Lucky that we got to know her’

A constant refrain in their conversation was how much the professors valued their opportunity to have a personal relationship with O’Connor and share in her remarkable legacy.

Banner: At the funeral, when I was talking with the other clerks, we all were saying that we feel lucky that we got to know her. I feel very lucky that I got the opportunity to spend a year with her.

Bussel: It’s a great privilege clerking for any justice of the Supreme Court, and if you have that opportunity, it’s an opportunity that you should seize, whoever it is. But I think I got like a cherry on top by clerking for Sandra Day O’Connor. Not because she was the first woman, but because of who she was as a person, as a judge.

Anabtawi: I felt very inspired by the opportunity to work with her. Justice O’Connor made history, and she was an inspiration to all law students, then and today, and she will be forever. It’s not just because she was the “first,” as her authorized biography is named. It’s also her life’s work, all of the challenges that she encountered and surmounted. She did that with grit but with grace, as well. There’s nobody I talk to, when I tell them that I had the opportunity to clerk for her, who isn’t in awe. That’s a legacy that I feel very privileged to be a part of. [All agree]

Volokh: When I think about O’Connor’s legacy, my sense is that, unlike some other justices, I don’t think she thought of herself as creating a legacy for the future, as trying to reroute the law in particular ways. I think she thought of herself as doing the best job she could under the circumstances. Dealing with the cases that arose. She wasn’t interested in there being a future understanding of some O’Connor approach to the law, or O’Connor Doctrine. What she wanted to leave is a body of work well done.

Bussel: And the epitaph, “Here lies a good judge.”