Jon Michaels discusses the rise of political violence

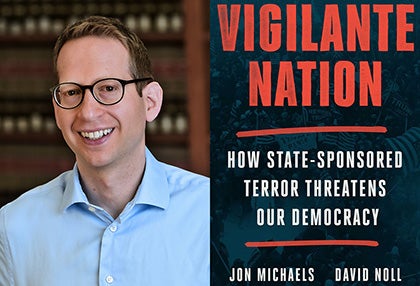

With recent politically motivated murders in New York, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C., and other attacks in Colorado and Pennsylvania, acts of political violence appear to be on the rise. This state of affairs is no surprise to UCLA School of Law professor Jon Michaels — an authority in constitutional law, administrative law, and the separation of powers. His recent book Vigilante Nation: How State-Sponsored Terror Threatens Our Democracy (Simon & Schuster/Atria, 2024), which he co-wrote with David Noll, explores the causes, effects, and long-term impact of this spike in political violence. Here, Michaels, who clerked for Justice David Souter on the U.S. Supreme Court, talks about the themes in his book and how they relate to current events.

With recent politically motivated murders in New York, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C., and other attacks in Colorado and Pennsylvania, acts of political violence appear to be on the rise. This state of affairs is no surprise to UCLA School of Law professor Jon Michaels — an authority in constitutional law, administrative law, and the separation of powers. His recent book Vigilante Nation: How State-Sponsored Terror Threatens Our Democracy (Simon & Schuster/Atria, 2024), which he co-wrote with David Noll, explores the causes, effects, and long-term impact of this spike in political violence. Here, Michaels, who clerked for Justice David Souter on the U.S. Supreme Court, talks about the themes in his book and how they relate to current events.

What is political violence?

Political violence involves the exercise of private coercive force to effect political or legal change; it represents a stark and alarming contrast to the ways in which democratic societies ordinarily operate — namely, through advocacy, campaigns of persuasion, and competitive elections. In essence, those committed to political violence seek to transform the airy marketplace of ideas into a dark alley of violence, where menacing actors punish dissenting views. Making an example of some, these vigilantes hope to deter many others from voicing their dissenting views and discourage even more from engaging in civic participation altogether. Thus, though the violence is most literally and viscerally perpetrated against individuals or groups, there is also considerable harm done to our civic, democratic, and legal institutions because the specter of violence makes it much harder for those institutions to carry out their missions.

Hasn’t this always happened in the United States?

Political violence has a long and brutal history in the United States, in no small part because the perpetrators of violence enjoyed the support of influential figures in law and politics. The first third of my book covers this history up until the mid-1960s, emphasizing its particular importance in entrenching and enforcing first American slavocracy and then the Jim Crow regimes of postbellum South. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 — and a federal commitment to enforcing those rights, support for political vigilantes waned considerably. Many believed, or at least hoped, that this new era in which we were finally becoming a truly inclusive democracy — and violent saboteurs were given no quarter — would extend indefinitely. But, as the middle third of my book shows, over the past 10 years, there is surging support and renewed enthusiasm for political violence.

What’s new or different now?

What’s particularly striking now is that we are normalizing, excusing, and even celebrating acts of violence and vigilantism, justifying heinous, reprehensible acts if the cause is deemed sufficiently righteous — or, as some might believe, the targets deserve it. For years, the culture warriors prosecuting and defending vigilantism were on the far right, which is fully consistent with past projects tied to white supremacy. Prominent examples include Kyle Rittenhouse, acquitted of killing two and wounding a third at a 2020 racial justice protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin; the January 6, 2021, insurrectionists, whom President Trump has since pardoned; militia groups that bullied their way into positions of power and influence in various local jurisdictions, including some in California; and individuals and groups — most of whom were never arrested, let alone prosecuted, who threatened and harassed voters, election administrators, and legislators in an effort to disrupt or overturn the 2020 election.

While the June 2025 murderous attacks on high-ranking Democrats in Minnesota, which resulted in the killing of a state legislator and her husband, and the campaigns of harassment and intimidation of judges viewed as hostile to the MAGA movement are a reminder that rightwing violence endures, there is evidence that these tactics are also being embraced by some on the far-left who, among other things, have sought to minimize or justify Luigi Mangione’s midtown Manhattan execution of the CEO of UnitedHealth and Elias Rodriguez’s gunning down of a young, presumptively Jewish couple leaving an event at a Jewish museum in Washington. Mangione allegedly felt betrayed by the for-profit health insurance industry, and Rodriguez reportedly claimed he “did it for Palestine.” Add to the mix the attempted arson of Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro’s home, during a Passover Seder, by an individual who blamed Shapiro for deaths in Gaza; the Boulder, Colorado, firebombing of a group keeping vigil for the hostages held in Gaza; and, most recently, the apparent effort to run Ohio Rep. Max Miller off the road, by a driver allegedly shouting antisemitic slurs and threatening to kill the Republican lawmaker and his young daughter.

Why are we seeing this resurgence?

The reasons are manifold. With respect to rightwing violence, it may be partly a wildly disproportionate backlash to the progress we made along lines of race, gender, and sexual identity — and concomitant fears that newly empowered groups threaten the old order dominated by white Christian men. It may also be a byproduct of a political culture that fetishizes gun rights, views all sorts of legal — and democratically arrived at — government actions as acts of oppression, and mythologizes those who take up arms against supposed government tyranny.

For those on the far-right and perhaps on the far-left, too, the increasing coarsening, polarization, and tribalization of our politics has turned “the other guys” — that is, those who identify with the other political party — into mortal enemies. Many report considerable disillusionment with American democracy, indulge conspiracy theories, and feel helpless when it comes to effectuating change through courts and elections. Any and all of these sentiments may lead the most alienated down the dark path of violence.

Where do you see us headed?

We are, I fear, headed for continued acts of harassment and violence because we’re so polarized and adversarial. So long as violence seems to fall along partisan lines, and we’re so bitterly divided, there will be those who condone, justify, or even celebrate the effort. Again this hurts individuals and groups, but also our democratic and civic institutions. I cover this in the last third of my book, which canvasses ways that Congress and the courts, private-sector actors, and state governments may help us regain our democratic footing.

Since publication, there is little sign of progress. Quite the contrary, things seem to be getting significantly worse, and thus I remain alarmed and troubled.

What, if anything, can we as individuals do?

Our democracy is constantly being tested. We focus considerable energy on threats to democracy from our nation’s leaders. Needless to say, we do so with good reason. Still, many of us ask ourselves, What can we do? How can we make a difference?

That’s a tremendously difficult question, but one thing is for certain: How we individually and collectively respond to acts of political harassment, aggression, and violence is itself a test. And it’s not just a test of our manners or morality. It’s also a test of our commitment to democracy and the rule of law.