“Gary Schwartz, a mentor, was brilliant and quirky, a voracious reader with a keen legal mind. He profoundly shaped tort doctrine through his scholarship and through his work as a reporter on the first part of the mammoth Restatement (Third) of Torts for the American Law Institute.”

Richard Hasen on Gary Schwartz

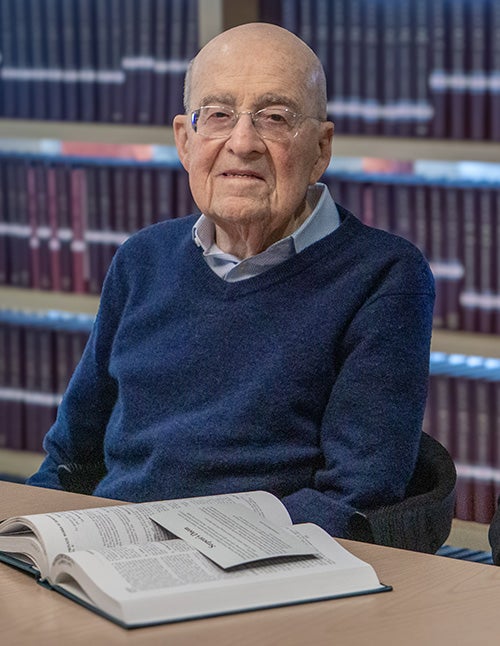

Arthur Greenberg and Joseph Tilem, members of UCLA Law’s very first class, look back on their time in law school and extraordinary careers.

A law school at its start

Tilem, now 98, was a UCLA undergrad when he heard that a law school was opening. He walked across campus and found someone taking the names of those wanting to be considered for admission. “I put my name down and later was pleased to learn I was accepted,” he said.

Greenberg wanted to go to law school at Stanford, where he had spent his undergraduate freshman year before transferring to UCLA, but his parents wanted him to stay close to home. Although his family lived near USC, Greenberg chose UCLA Law.

Watch "A Conversation with UCLA Law's Inaugural Class" and join Dean Michael Waterstone as he sits down with Arthur Greenberg and Joseph Tilem, alumni from UCLA Law's historic first graduating class of 1952. In this conversation, Arthur and Joe both share their memories of early campus life, reflect on their distinguished careers, and discuss how their UCLA Law education shaped their professional journeys.

Both men — two of the last living members of UCLA Law’s very first class — had vivid memories of the school’s early days. “For two years, we had classes in barracks — like the ones I slept in the army — behind Royce Hall,” Greenberg recalled.

Tilem chimed in: “Yeah, there was a room where we could spend spare time, and a few of us would occasionally play cards there, with nickels, dimes, and quarters. But it all came to a halt when Dean Coffman came through, giving a tour to deans from other law schools. We were chastised, and the next day, an edict went out: ‘No card playing.’”

The two remembered the school’s first dean, L. Dale Coffman, as “running a tight ship.” He was “tough, not particularly friendly,” Greenberg said.

In a class of 49 men and five women, the top two students were female. It was, Tilem noted, “the great irony.”

Classes met six days a week at 8 a.m. The men agreed that there was no time for a social life; they were “glued to the books.” They took notes in class “furiously” and typed them up at night. “You’d summarize the lecture into 10 lines on a tissue paper that was gummed on one side, and stick it into a notebook,” Tilem said.

The construction of a building was a major milestone for the new school. Both men remember watching it go up “brick by brick.” When it opened, “it was kind of shocking to walk into it,” Tilem said. “Some of the doors didn’t open properly. There were a lot of little things that still needed work. It had an enormous library, and I got a job there, putting books on the shelves for $1 an hour.”

“Don’t focus too narrowly on one thing, because something is going to come in from left field. It’ll change your life. It did mine.”

Their careers take flight

After graduating, Greenberg joined a firm in down- town Los Angeles at a salary of $400 a month. His partners were specialized, focused only on certain types of cases, so he tried to handle everything else — “whatever walked through the door.”

In questioning prospective jurors for his first case, he knew he wasn’t supposed to ask a woman if she was married. “So I said, ‘Mrs. Smith, is there a Mr. Smith?’ She answered, ‘Yes, there are many.’”

In 1959, he joined attorneys Philip Glusker and Irving Hill in forming Greenberg Glusker above a Safeway store on Wilshire Boulevard. Hill, the most experienced of the three, charged $30 an hour; Glusker and Greenberg, $25. Today, the firm— now in Century City — charges $1,000 an hour.

As for Tilem, in his second year of law school, he was hired as a law clerk at a firm on South Beverly Drive, for 90 cents an hour. “I really just filled the paper machine and cleaned up in the office,” he said. “When I passed the bar, they raised me to a dollar an hour.”

But his fortunes changed when he got a call from one of the firm’s clients, Alfred Bloomingdale, owner of Diner’s Club, which created the world’s first multipurpose credit card. Bloomingdale invited Tilem to work for him for $600 a month. “I felt it might be disloyal to leave the firm with a client, so I called my father for advice. But I couldn’t forgo the salary, and I was at Diner’s Club from 1954 to 1960.”

Then, when Hilton Hotels started a credit card company, Barron Hilton hired Tilem as vice president. In that role, he traveled to South America, Europe, and the Middle East, trying to get banks to accept the Hilton card.

Next, Tilem started his own law firm, which grew to 11 members. He started another new chapter when he was elected mayor of Beverly Hills. He recalled, “Being mayor was like taking a postgraduate college education in dealing with street lighting, union negotiations, what kind of trees you’re allowed to plant in a city, and a whole range of human activities that you would never encounter in any other way except when you’re in the hot seat at city hall.”

Tilem and Greenberg reconnected occasionally over the years. Notably, they crossed paths when Greenberg Glusker handled the savings and loan crisis in L.A., which Greenberg remembered as a “very bitter, tough experience.” Tilem, who at the time was on the board of a failing savings bank, remembers being deposed by Greenberg. “I was scared,” he admitted. “It’s very different when you’re being deposed rather than taking the deposition.”

UCLA Law’s lasting impact

“Arthur and I went in very different directions,” Tilem said, “but the nucleus of our life experience has been based on what we did in law school. Sometimes, years later, a case you had in school applies to what you’re doing.”

He said UCLA Law taught him the importance of working together by partnering him with a classmate to study for the bar exam. “That taught me the need for talking with your colleagues,” he said. “As a result, later in my law practice, I had no problem walking into my partner’s office to discuss a case.”

Asked what advice he’d give to graduating students today, Tilem said: “Keep your options open. So much of it is serendipity. You never can tell when opportunity is going to arise. Don’t focus too narrowly on one thing, because something is going to come in from left field. It’ll change your life. It did mine.”

Greenberg advised: “Be careful in choosing where to practice law. Some firms are better than others in how they treat people. That’s a serious issue. But the law practice to me was exciting, interesting, profitable, and happy.”

Read more in the 75th Anniversary edition of the UCLA Law magazine.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.

A Groundbreaking Appointment

Susan Westerberg Prager | 1982-98

Dean Prager entered UCLA Law as a student in 1968. In 1982, she became the first female dean of the law school— one of only two in the country.

“I was surprised at how warmly I was welcomed, especially by the older alumni,” she said. Because she had been on the faculty since 1972 and had served as associate dean to Dean William Warren, people within the school already knew her well.

Tough Challenges, Fun Times

Jonathan D. Varat | 1998-03

Two years before Dean Varat’s appointment, California adopted Proposition 209, decreasing student diversity. But, Varat said, “invigorated outreach and recruitment” at UCLA Law restored a diverse student body. Although the national financial crisis in 2000 required fiscal belt-tightening, the school kept moving forward. Following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, Varat’s primary concerns were assuring the well-being of students and alumni and maintaining a caring school environment, one “not subject to inappropriate reactions.”

Some of the fun times: the dean’s annual backyard barbecue for first-year students and a student fundraiser that charged a fee to drop Varat into a dunk tank. Former Dean Richard Maxwell teased Varat, saying he himself had never done “swimming for dollars.” Other highlights Varat recalled include joining a student-organized event with former Vice President Al Gore, welcoming former Secretary of State Warren Christopher as commencement speaker, and having Leon Panetta present for the 50th anniversary of the law school.

Varat saw the school as “a home, a family, an extraordinary place of intellectual engagement, where remarkable people come together to better education, justice, and humanity. Our students, faculty, alumni, and communities are the heart and soul of what we do.”

Overcoming Obstacles, Making Friends

Michael Schill | 2004-09

During the Great Recession of 2008, Dean Schill worried that gifts to the school would “precipitously decline.” During this time, he remembered driving home from a basketball game with alumnus David Epstein ’64, who had recently made a large gift to name the Epstein Program in Public Interest Law and Policy. On the drive, Epstein said that despite significant losses in the market, the gift was the best thing he had ever done.

“I was so happy,” Schill said, “because that is what you want as a dean— to accomplish something meaningful for both the donor and the school. Giving remained strong, which reflects the great love that alumni have for the school.”

He averted a crisis early in his tenure, when 10 faculty members had offers to go elsewhere. “If we were to maintain our prominence as one of the great American law schools, we needed to retain them,” he said. Working with Ann Carlson, he managed to keep almost all of them, and most of them remain on the faculty.

Schill treasured the friends he made at the school, among them two people he continued to speak with almost every week for many years thereafter. “I quite unexpectedly gained a second set of parents in Ralph and Shirley Shapiro,” he said. “I will always love them deeply.”

A Community of Excellence

Rachel Moran | 2010-15

“UCLA Law’s strength comes from its people— students, faculty, staff, alumni, and friends,” Dean Moran said. “Each year, all the incoming students are academically accomplished, but many also have achieved distinction in other fields. I remember one who took a leave of absence to perform on Broadway in In the Heights. After a rewarding run, he finished his J.D. and sang at graduation.”

From the dean’s office, Moran got a bird’s-eye view of the school’s many constituencies. She said that while they held different visions and aspirations, all were “committed to academic excellence and the belief that law can make a difference. They shared a responsibility to use law for good.”

One of Moran’s great pleasures was “recruiting faculty to join this outstanding intellectual community. I also was happy — and relieved — to fend off many efforts to poach our illustrious faculty.”

At first, Moran was reluctant to ask donors for gifts, but she knew that this was part of being dean. “I was trained never to ask for money,” she said. But once she recognized that she wasn’t asking for herself but “for a great institution,” she found ways for donors to make “satisfying investments that advanced the law school, legal education, and the state of law itself.”

Adaptation, Growth, and Achievement

Jennifer Mnookin | 2015-22

When the pandemic hit in 2020, “UCLA Law had to pivot almost over- night to remote learning, and, well, remote everything,” Dean Mnookin said. “It was hugely challenging, but also inspiring to see our community being so creative, persevering, and nimble in tremendously difficult circumstances.” She said that what made UCLA Law so special before, during, and after that time was “the deep sense of community, the incredible focus on training students to be exceptional lawyers and leaders, and the faculty, staff, and alumni commitment to excellence and to each other.”

Buoyed in significant part by record fundraising, the law school established many new centers and institutes during Mnookin’s tenure as dean. New experiential learning opportunities for students were developed, among them the Immigrant Family Legal Clinic, the Documentary Film Legal Clinic, and the Veterans Legal Clinic. Also launched under Mnookin’s leadership was the cutting-edge Master of Legal Studies program.

“The U.S. News rankings need to be taken with a large — giant! — grain of salt,” Mnookin said, “but I confess that I’m proud and grateful that we broke into the T14 during my time as dean. But I’m even prouder of the amazing faculty we hired and retained and the students whose careers we launched.”

Though she is now chancellor of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Mnookin remains a Bruin for life. “I learned so much from colleagues at the law school and across campus and made lifelong friends,” she said. “I’ll root for the Bruins against anyone except the Badgers!”

Interim Deans

Norman Abrams | 2003-04

Norman Abrams | 2003-04

“I came to the law school in 1959. It has grown from a faculty of 12 to one of over 70; from a school with no national presence to being one of the leading schools in the nation; a school marked by innovative programs in research and clinical practice and centers of excellence in many fields; a school that even as an emeritus professor, I still take pride in being part of.”

Stephen C. Yeazell | 2009-10

“I’ve been privileged to teach at the school since 1975 and can say that it and the surrounding campus— and the other UC campuses— are an extraordinary collection of students, faculty, and staff. Both within the school and on the broader campus, I have witnessed a humbling level of creativity, goodwill, and inspiration. Colleagues, students, and staff have encouraged, inspired, and supported me for what will be 50 years. I am grateful beyond words.”

Russell Korobkin | 2022-23

“There is no question that the best day of the year was graduation. At the ceremony, more than 550 J.D., LL.M., and M.L.S. graduates felt intense pride in themselves and appreciation for the institution that had helped them get to that place. Having the opportunity to represent the law school, both sharing a few words of wisdom with the graduates and their families and shaking the hand of each graduate as they received their diplomas, was truly an honor that I will never forget.”

Read more in the 75th Anniversary edition of the UCLA Law magazine.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.

UCLA School of Law opened its doors on September 19, 1949.

The million-dollar tent

UCLA Law has always been a big tent. In the 75 years since it opened in a city of excitement and energy, the law school has grown boundlessly. It has expanded generation by generation, while remaining firmly rooted in its original purpose — to be a place of opportunity, courage, and unwavering openness to new ideas, new colleagues, new ways of going about legal education, and new ways of uplifting students, causes, and communities around the world.

Through the years, well over 20,000 students have earned degrees at UCLA Law. Thousands more have served the community as members of the faculty and staff or as friends whose gifts have been immeasurable. Each one has shared that spirit of service and collegiality — and that instinctive drive toward excellence— that quickly came to characterize the new law school in the booming city several hundred miles south of San Francisco and Sacramento.

Dorothy Wright Nelson ’53 was one of the first people to carry that tradition. Years before she became a trailblazing law school dean and judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Nelson was one of the local kids whom Rosenthal had in mind. Born in San Pedro to a teacher and a building contractor, she earned her undergraduate degree at UCLA and entered the law school in its second class. There, she found guidance and grace when she struggled through the start of her legal studies — as well as a touchstone sense of fairness.

One mentor, she recalled, “said something that affected my whole career choice: ‘It doesn’t matter what the law is if the access to justice isn’t there. If the procedures keep people from having access to true justice, the system won’t work.’” She noted that she saw the sentiment repeated in the many clerks whom she hired from UCLA Law over the years. “That was embedded in my whole psyche at UCLA, and I’m very grateful.”

Even as UCLA Law’s ethos solidified during its first decade, the early years were marked by tumult under its inaugural dean, L. Dale Coffman, whose autocratic style led to a faculty revolt and his subsequent removal in 1958. That moment set a tenor that has characterized the law school ever since, recalled Norman Abrams, who joined the faculty in 1959 and later served as an interim dean of the law school and acting chancellor of UCLA. “Out of that period of turmoil, civility grew as a faculty value,” Abrams said. “A very strong sense of a shared community and getting along with one’s colleagues also became and have remained hallmarks of the school.”

Growth abounded through the leadership of the two deans who came next, Richard Maxwell and Murray Schwartz. Everything — from the number of people on the faculty to the number of volumes in the library to the reputation of the young institution — expanded.

“We became, within 10 years, a well-regarded law school, nationally well-regarded,” remembered the next dean, William Warren, who came to UCLA Law in 1959 after having departed the legal establishment in Illinois. “Opportunity here seemed greater than that anywhere else, and optimism was running over. And, I must say, I was swept up. … This is where the future is going to be.”

Renowned constitutional scholar Kenneth Karst was similarly pleased when he traveled from Ohio to join the faculty in 1965. “There are people here who provide a kind of … spiritual or emotional support, who want you to do well at what you do and want to help in any way they can, and they convey that by their manner,” Karst said. “We’re very lucky. … There is a sense of community around here that is very warming and enriching.”

Students felt it, too. Steve Lachs ’63 — who would later become the first openly gay judge in the world— was boosted by UCLA Law’s vibrancy and robust collection of people who made connections and got things done. It was, he said, “a dynamic and growing school. You could feel it. This was not a school that was just going to be sitting there. It was moving. And it was a good feeling to be a part of that.”

“Optimism was running over. And, I must say, I was swept up. … This is where the future is going to be.”

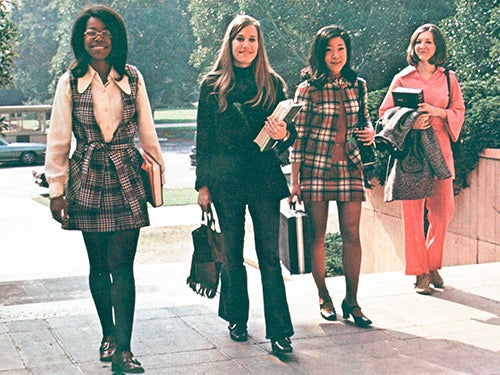

Emboldened by this steadfast commitment to progress, members of the UCLA Law community adapted notably faster to the times, when the broader society was gripped by radical change, than their counterparts at other institutions. The idea of rebellious lawyering in the public interest, of shaking up the standards that had bound legal education for far too long, took hold. UCLA Law was early in hiring women and people of color as professors. In 1966, the law school introduced the Legal Education Opportunity Program (LEOP) to bring in large numbers of students from underrepresented groups. The National Black Law Journal launched in 1970.

“UCLA Law had developed a reputation for inclusiveness,” remembered Carole Goldberg, who joined the faculty in 1972, a few years after the law school hired Barbara Brudno as its first woman professor. “When three females, including me, all agreed to accept UCLA’s offer, we were the talk of legal education. No major law school at the time had more than one woman on the faculty, if that. As the years passed, all three of us”— Goldberg, Susan Westerberg Prager ’71, and Alison Grey Anderson— “became tenured professors.”

Goldberg went on to enjoy a groundbreaking career as an administrator and one of the nation’s most prominent scholars of Native American law. “I have benefited from the law school’s empowering receptivity to new ideas and new areas of teaching and research,” she said. “To this day, my field of study has not been incorporated into the curriculum of many major American law schools. But because of UCLA Law’s deeply engrained spirit of innovation, I received a positive response whenever I developed new programs.” That positive spirit reverberates for alumni as well, long after they leave Westwood.

“Being at UCLA Law helped build the foundation for my career as a civil rights lawyer and law professor,” said Janai Nelson ’96, who, as the president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF), is the top civil rights attorney in the country. Through UCLA Law, she first externed with LDF and made invaluable connections with her Black professors, colleagues on several journals, and fellow members of the Black Law Students Association. “It’s hard to imagine surviving law school without those friendships and supports. The racial and ethnic diversity of the student body was one of the law school’s greatest strengths.”

After she graduated from UCLA Law, Antonia Hernández ’74 also embarked on an inspiring career of impactful service, including as the longtime head of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and the California Community Foundation. “UCLA Law, in many ways, through individual professors and deans, has tried very, very hard to really set itself aside and say, ‘We’re an L.A.-based institution, and we want to reflect the diversity of the place we’re in,’” she said. “I have to give them credit for that. I think that’s one of the reasons I have stayed connected and involved, because I do see the effort. I see them understanding it.”

Open for innovation, open to the world

Melville Nimmer was a respected lawyer when he joined the UCLA Law faculty in 1962. A year later, he published the first parts of his seminal treatise, Nimmer on Copyright, which remains the key practical guide on one of the most significant areas of the law — and quite possibly the most enduring work of scholarship ever to be born at the law school.

Three decades later, Ken Ziffren ’65, who studied as a law student with Nimmer, wrote about the insight and foresight that caused Nimmer’s celebrated work — which presaged issues in forms of media that had yet to be fully conceived — to come to life at UCLA Law. “He challenged befuddled students, academics, practitioners, and judges as no one had before,” Ziffren wrote.

It was a fitting summary of a culture of innovation that naturally sprang from the law school’s essential openness— a style that certainly inspired Ziffren, who pivoted from initial work in tax law to a pioneering career as an entertainment law luminary. He and other alumni would go on to help establish UCLA Law as the country’s top school for entertainment law. And, like so many successful graduates, he would give back in countless ways over the years, among them teaching and mentoring students and founding the Ziffren Institute for Media, Entertainment, Technology and Sports Law.

Not content to rest easy in the comfort of their community, other people from across the law school have branched out to meet the moment— in education, in scholarship, in contending with society’s biggest challenges, and in connecting with their colleagues around the globe.

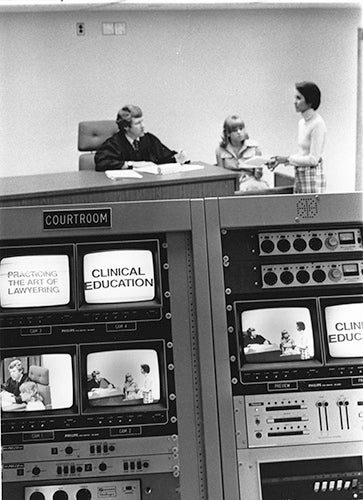

Starting in the early 1970s, that meant the launch of the law school’s pathbreaking clinical education program, which seizes opportunities to help real-world clients while teaching practical lawyering. “A lot of people went to law school in order to change society for the better,” remembered Paul Bergman, who co-founded the program. “They wanted an opportunity to do that while they were in law school. But what differentiated UCLA Law was that we primarily wanted to train lawyers not in legal analysis but in using legal skills, which the law school curriculum otherwise basically ignored. It was all about principles and reasoning and argumentation. But how do you work with clients?”

That global perspective— the kind of work that is done with an eye on places far beyond the classroom or California— has endured.

“A very strong sense of a shared community and getting along with one’s colleagues also became and have remained hallmarks of the school.”

In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw used the term “intersectionality” in an article titled “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” It remains a landmark work of scholarship and is a stark example of the profound ways in which the UCLA Law community came together to grapple with one of the most pressing issues.

And it is something that Crenshaw, a national leader in civil rights law and co-founder of the trailblazing Critical Race Studies program, said could really have only happened at UCLA Law. “‘Demarginalizing’ was my second article, but it was barely a draft when I joined the faculty,” she said. The faculty “fully embraced scholarship that pushed the envelope, so although I knew I was writing against the grain, the signals within the building were encouraging. Indeed, the mentoring offered by colleagues here was more than I could have possibly expected. Overall, my decision to come to UCLA is an important— perhaps even a ‘but for’— factor in the emergence of intersectionality in legal theory.”

But for UCLA Law

But for UCLA Law, researchers at the Williams Institute would not have had their work undergird the Supreme Court’s opinion on marriage equality. But for UCLA Law, students and staff with the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment would not have contributed to legislation that combats the devastation of climate change. But for UCLA Law, members of the Lowell Milken Institute for Business Law and Policy would not be producing impactful work on corporate law, bankruptcy, taxation, and more. But for UCLA Law, the people of The Promise Institute for Human Rights would not be on the front lines of the fight for human rights in places far from home.

And but for UCLA Law, new generations of students— J.D., LL.M., M.L.S., and S.J.D. alike — would not receive a legal education that is geared, quite simply and quite explicitly, toward improving lives.

Ariane Nevin LL.M. ’15 came to UCLA Law on a Health and Human Rights Fellowship after receiving her law degree in South Africa. Looking to become a more effective social justice practitioner, she scanned public interest programs at American law schools and landed on UCLA Law, where she recognized the names of several faculty members and instantly got excited by the idea of studying with them as an LL.M. student.

“I was completely blown away,” she marveled when she looked back on her experience and how it enhanced her work for prisoners and others in South Africa. “UCLA Law definitely affected the way that I practice. It’s given me a much more sensitive approach to advocacy, and it boosted my confidence. Coming back to practice [in Africa] with UCLA Law behind me makes me a more confident, stronger advocate.”

Ever strengthening. Ever evolving. Ever rising. At UCLA Law, for the 75 years that we celebrate today and for the 75 years to come: All rise.

“Our legacy and our future are one and the same,” said Michael Waterstone, the 10th and current dean of the law school. “We embrace visionary scholars, we educate and empower the brightest students, and we excel in carrying out our greatest tradition: creating bold new approaches to solving problems. I can’t wait to see what the next 75 years have in store.”

Read more in the 75th Anniversary edition of the UCLA Law magazine.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.

When the U.S. Supreme Court decided the case of Thompson v. United States in March, the justices’ unanimous decision brought relief for the defendant in the matter – and it was the latest victory for members of UCLA School of Law’s Supreme Court Clinic.

For Ellen Park '26 and Aniq Chunara '26, spending a semester in The Hague, Netherlands, was more than an ordinary academic experience, it was a transformative immersion into the hub of international justice.

The Colorado River — a vital water source for 40 million people in the Southwest — is seriously imperiled by overallocation and the effects of climate change. The need to swiftly reform the use of Colorado River water is clear. That’s why NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council) along with a coalition of Waterkeepers and other local advocacy groups are asking the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to utilize its legal authority to stop the waste of Colorado River water in Lower Basin states, including California.

Air regulators today face complex challenges but also have enormous opportunities. This brief discusses a set of air regulatory tools that can help empower states and local air districts to do more to reduce harms caused by air pollution to communities.