26. VISITS FROM SUPREME COURT JUSTICES

26. VISITS FROM SUPREME COURT JUSTICES

Throughout the years, 11 Supreme Court justices have visited UCLA Law. In 2018, Justice Elena Kagan spoke to then-Dean Jennifer Mnookin about civility and the virtue of listening.

An innovative new partnership between UCLA School of Law’s Criminal Law and Policy Consortium (CLPC) and the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s Office (LACPD) will give individuals facing deportation legal representation from a UCLA Law graduate with deep experience in immigration or public interest law.

The guide is an invaluable resource for advocates who represent unhoused people facing steep financial and legal burdens for sleeping on streets and other basic human behaviors.

01. ALUMS WHO SHOW THEIR PRIDE

01. ALUMS WHO SHOW THEIR PRIDE

“I believe this photo shows that UCLA alums are establishing beachheads everywhere in the U.S.”

Greg Smith ’89 proudly displays his personalized Alabama license plate.

How the LL.M. and M.L.S. programs meet the needs of a global society and help UCLA shape the future of legal education

“The country needs people in leadership roles who understand how the law works, and not all of them need to have a three-year J.D. and a license to represent clients.”

Transforming legal education

Offering expansive opportunities for students from all backgrounds, UCLA Law has been moving legal education forward since the day it opened in 1949. Little more than 20 years later, the law school launched its robust clinical education program. And more recent decades have seen a shift further toward the future, with an emphasis on degrees and specializations that expand the reach of a UCLA Law education and diploma.

Today, professionals like Ip who want to learn the law and earn a UCLA Law degree without ultimately practicing law can join the M.L.S. program. At the same time, hundreds of lawyers come from around the world to pursue master of law (LL.M.) degrees, educating themselves in American law or specializing in an array of key areas of practice. These cohorts now make up a vital portion of the students who attend UCLA Law each year— and of the alumni who are able to impact their communities in transformative ways.

Russell Korobkin, the Richard C. Maxwell Distinguished Professor of Law and vice dean for graduate and professional education, was one of the visionary administrators behind this remarkable development. Expanding the menu of what a law school offers was at the top of his mind when he conceived of and launched the M.L.S. program in 2019.

“In the United States, law has traditionally been offered only as a graduate degree, which means that very few people in the business, nonprofit, and government sectors of the economy who are not credentialed lawyers have had any opportunity to study law,” he said. “In a world in which law affects virtually every corner of the economy, this is a really bad situation. The country needs people in leadership roles who understand how the law works, and not all of them need to have a three-year J.D. and a license to represent clients.”

People who earn LL.M. degrees also enjoy the opportunity to distinguish themselves in their careers. The program has been around for years, but it has grown rapidly in size and stature over the past two decades. It is designed for practicing lawyers who have already earned their law degrees, many of whom come from outside the United States to gain expertise in specialties that aren’t readily available in other countries.

“In a lot of countries, law schools provide legal training for private law practice,” said Lara Stemple, assistant dean for graduate studies and international student programs. “Depending on the country, there isn’t the norm that we have at UCLA Law of studying all areas of law and providing students the ability to do work in a huge range of areas. We’re seeding the field with young people who are well trained in topics of law that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to study.”

Broadening perspectives

Before he earned his LL.M. degree at UCLA Law, Juan Pablo Escudero LL.M. ’22 was an environmental attorney who advised former Chilean president Sebastián Piñera on climate change. After graduation, Escudero returned home, and he now teaches college courses in climate change law. He also works remotely for UCLA Law’s Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, researching how to craft better methane regulations for South American countries.

“UCLA taught me that there’s no one way of being a lawyer,” he said. “You can be focused on climate change, or you can do contracts and work for a mining company. It was a fascinating realization for me. I don’t think that there’s any place on Earth that understands environmental law, environmental advocacy, and environmental fighting better than UCLA, or better than California. The people who work there, it’s like playing in the most competitive sports league. This is where the big dogs are.”

Students in the M.L.S. program look at UCLA Law in the same way, and they view their degree as a key opportunity for career advancement.

Fifteen years ago, there weren’t even five M.L.S. programs nationally, said Jason Fiske, assistant dean of graduate studies and professional programs at UCLA Law. Today, there are 110 M.L.S. programs in the United States, and the number is expected to swell to 200 within five years.

UCLA Law faculty members began considering the idea when they understood that an increasing number of careers require at least a basic understanding of the law. But for the longest time, the only option was a J.D. degree. “The faculty knew that the law is too important to leave to just lawyers,” Fiske said. “The law impacts everybody. This provides access to legal education to people who don’t want to or don’t need to become lawyers.”

The school created an M.L.S. program with nine specializations. The most popular are in entertainment and media law, business law, and employment law. Now, M.L.S. graduates include entertainment executives who frequently negotiate contracts and licensing agreements, journalists who write news stories about complex legal matters, and executives who work in health care compliance.

This year, 130 students are enrolled in the M.L.S. program. The average member is 40 years old and already established in a career. Students have the option to take courses online or in person, and in a full- or part-time capacity. They are challenged by a rigorous curriculum that eschews classic law school courtroom preparation. “We just focus on the law aspects of the various topic areas,” Fiske said. “But nothing is taught lighter than it is in the J.D. program.”

“I don’t think that there’s any place on Earth that understands environmental law, environmental advocacy, and environmental fighting better than UCLA, or better than California.”

The LL.M. program similarly sees a set of students from a wide array of backgrounds. The program enrolls roughly 220 students per year, up from about 20 two decades ago, hailing from roughly 35 countries. LL.M. students specialize in popular tracks like business law and media, entertainment, technology, and sports law.

Importantly, the program also offers the Health and Human Rights Fellowship, allowing students from South Africa and other nations to come to UCLA to study global health, human rights, gender-based violence, and HIV-AIDS through a legal lens. Similarly, the Critical Race Studies Fellowship attracts students from countries such as Colombia and Brazil, giving them an understanding of racial justice and the tools to foster change in their home countries.

Many LL.M. graduates apply their new abilities in government, nonprofits, academia, and NGOs abroad, where they demonstrate a particular hallmark of a UCLA Law education: writing in the American legal style and using clear, uncomplicated, and consistent verbiage.

For foreign lawyers who may spend five or more years in private practice before pursuing an LL.M. degree, their time at UCLA Law is “seen as a very pivotal year,” Stemple said. “It helps to show that you’re a global practitioner, that you can spend a year in an English-speaking environment. And then when you return, you have a higher status within a law firm. That’s kind of baked into the law firm trajectory in those countries.”

A life-changing opportunity

As UCLA Law marks its 75th anniversary, it enjoys the ongoing involvement of more than 20,000 living alumni, a considerable number of whom now hold LL.M. and M.L.S. degrees. Like the generations of J.D. students who have come through the law school, these professionals and attorneys know well the value that a UCLA Law degree carries, in every kind of career and all over the world.

“In Latin America, UCLA is a name that doesn’t require any explanation,” Escudero said. “People know right away the brand you’re talking about.”

For his part, Ip recalls his time at UCLA Law as a significant turning point in his career, a moment when he was surrounded by “a lot of folks who had lots of lived experiences to share in the classroom.” More still, it was an experience that he will forever credit as a big part of his success.

“I started the program and immediately found immense value,” he marveled. “It has changed my life trajectory.”

Read more in the 75th Anniversary edition of the UCLA Law magazine.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.

-

LL.M. Program

-

Master of Legal Studies

UCLA Law is grateful to funders who support our institutes, centers, and programs.

A. Barry Cappello Program in Trial Advocacy

Named for alumnus A. Barry Cappello ’65 in recognition of his generous 2017 gift, this program enhances trial advocacy training and provides scholarships for aspiring trial lawyers.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.

Launched over 50 years ago, UCLA Law’s clinical program— widely credited as the first of its kind— lets students put their lawyering skills to work on behalf of real clients.

“Our wide array of clinics provides students diverse opportunities to learn while effecting real change,” said Nina Rabin, director of the program. “As innovators in this area, we have created clinics that give students exposure to a broad range of substantive areas and advocacy methods, all of which are making a difference in people’s lives locally and globally.”

“This class is everything that law school should be. It embodies the ideal that the best way to learn is to do.”

Supreme Court Clinic

All law students study U.S. Supreme Court cases, but those in UCLA Law’s Supreme Court Clinic actually help represent clients. Just this year, their efforts led to a unanimous victory in Thompson v. United States, in which the Court held that a defendant cannot be convicted under a statute prohibiting false statements if his statements were merely misleading but not false. The students also persuaded the Court to hear an appeal in Villarreal v. Texas, which Professor Stuart Banner will argue in the fall. The issue in Villarreal is whether the Sixth Amendment right to counsel guarantees defendants the ability to discuss their testimony with counsel during overnight recesses. For these cases and many others since 2011, students have researched and written briefs. “It’s the kind of experience that few lawyers encounter, and I learned so much from the process,” said clinic student Albert Tian ’25.

Prisoners’ Rights Clinic

Arguing before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, students in the Prisoners’ Rights Clinic helped advance civil rights claims brought by a client who was blinded in one eye after cataract surgery and another who was severely beaten by other prisoners after officers failed to protect him. “Students come to understand that prisoner plaintiffs deserve first-rate lawyering, and that with very hard work, they are capable of providing it,” said Professor Aaron Littman, clinic founder and faculty director. Indeed, they are: The clinic secured victories in all five of its cases decided in 2024. After writing briefs for two of those cases as a student, Joe Gaylin ’24 — now a federal district court clerk— said, “This class is everything that law school should be. It embodies the ideal that the best way to learn is to do.”

“The opportunity to now use my education to help advance policies that protect the rights of immigrant communities like mine is a full-circle experience.”

Immigrant Family Legal Clinic and Immigrants’ Rights Policy Clinic

Winning an asylum claim for a young adult with severe mental illness was a particularly sweet victory for the law students at the Immigrant Family Legal Clinic, which serves the students and families at the RFK Community Schools in Koreatown. Previous clinic students had obtained humanitarian visas for the client’s mother, who was a victim of human trafficking, and four younger siblings. This is just one of the many success stories from the country’s only immigration law clinic that’s located on a K-12 public school campus. Clinic students help families at the school obtain residency, earn visas, gain work authorization, and more. “I would recommend the clinic to anyone interested in learning about immigration law and making a difference in students’ and their families’ lives,” said Lauren Kiesel ’20.

Students in the Immigrants’ Rights Policy Clinic lead research and advocacy to support immigrant communities in California. The work is especially meaningful to Soraya Morales Nuñez ’26, a former DACA beneficiary whose clinic efforts are focused on preserving state sanctuary laws. “The opportunity to now use my education to help advance policies that protect the rights of immigrant communities like mine is a full-circle experience,” Morales Nuñez said.

Community Lawyering in Education Clinic

Students in the Community Lawyering in Education Clinic are working to address inequities in the child welfare reporting system through projects that challenge the use of predictive algorithms and the targeting of low-income people of color.

“Clinical education is really valuable because it gives students a chance to figure out their own solution to problems.”

Human Rights Litigation Clinic

“Clinical education is really valuable because it gives students a chance to figure out their own solution to problems,” said Cathy Sweetser, director of the Human Rights Litigation Clinic. The approach is working. Clinic students brought a class action lawsuit challenging the use of force by private contractors against immigration detainees. A hearing is currently pending in federal court.

Veterans Legal Clinic

Appealing benefits claims, resolving landlord-tenant disputes, and clearing criminal records are just some of the ways Veterans Legal Clinic students have supported veterans. “Working on behalf of clients who truly needed dedicated representation helped me bridge the gap between legal theory and real-world advocacy and was the most meaningful part of my time at UCLA Law,” said Army veteran Gabriel Henriquez ’25.

Patent Clinic

When Beeline Wheelchairs needed a patent for the design of their invention of a low-cost, customizable wheelchair constructed from old stop-sign posts, the Patent Clinic took them on as a client. The result, “System for Construction of an Adjustable Wheelchair and Method of Using the Same” (U.S. Patent No. 9,974,703), is just one of the 26 issued patents that students have obtained for nonprofit pro bono clients. Students screen and select clients and draft and file their applications. “We receive hundreds of emails requesting representation and select clients who are traditionally excluded from access,” said Eugene Chong, director of the clinic.

“Working on behalf of clients who truly needed dedicated representation helped me bridge the gap between legal theory and real-world advocacy and was the most meaningful part of my time at UCLA Law.”

Street Law Clinic

“Street Law Clinic has been my favorite class I have taken in law school,” said aid Alondra Ulloa ’25 of her experience teaching legal topics to Los Angeles high school students— many of whom may have had negative experiences with the law. “[Having] my students ask critical questions, challenge ideas, and even express interest in pursuing legal careers was incredibly rewarding for them and educational and empowering for me. It reminded me why I chose this path in the first place: to make the law more accessible, and to help others see it as a tool for empowerment rather than just a source of harm.”

Mediation Clinic

Nica Aranaga ’25 calls working in the Mediation Clinic the most rewarding part of her legal education. She and her fellow student mediators help couples navigating the divorce process divide property, decide on parenting plans, and discuss spousal and child support obligations. But the clinic benefits go beyond the legal skills learned. “It has taught me how to listen carefully, respond intentionally, and help clients reach meaningful resolutions, even in highly charged situations,” Aranaga said. “I never expected to develop this kind of interpersonal skill in law school, and I know it will serve me throughout my legal career.”

Talent and Brand Partnerships / Name, Image and Likeness Clinic

Helping score deals is more than a game at the new Talent and Brand Partnerships / Name, Image and Likeness Clinic, where law students advise UCLA student-athletes on licensing, merchandising, branding, and endorsement matters during team presentations and one-on-one clinic sessions. This win-win collaboration between the law school’s Ziffren Institute and UCLA Athletics helped UCLA earn a 2024 NIL Awards nomination for Best Institutional NIL Program.

Read more in the 75th Anniversary edition of the UCLA Law magazine.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.

A look inside UCLA Law’s robust centers of scholarship and advocacy, which have expanded the law school’s influence on the most important issues of the day.

“The fact that we’re among the youngest major law schools in the country means that we have the freedom to build new ways of training lawyers.”

As those programs reach their quarter-century, at a moment that happens to fall around the law school’s 75th year, their influence on UCLA Law’s identity is clear. The launches of CRS and the Williams Institute— and, a few years later, the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment — marked inflection points for UCLA Law. The school had been creating world-class lawyers for decades, but the turn of the 21st century brought about a bold shift in thinking about what else a leading law school should offer.

Thanks to the immense contributions of alumni donors and other philanthropic partners in the com- munity, more centers of scholarship emerged before long, all of them building on the model of engagement and scholarship that CRS, Williams, and Emmett had established. Now numbering more than two dozen, the centers encompass a panoply of disciplines. Each was established with a mission to drive change through academic rigor, specialized training, and issue advocacy— and each made an immediate impact while boosting the school’s reputation and galvanizing its intellectual core.

Today, these centers are at the heart of the UCLA Law experience, amplifying the research of faculty members and top experts in an array of fields, informing policymakers in the United States and around the world, and offering students unparalleled experiential educational opportunities. The collective scope of these projects underscores a scholarly dynamism that has existed at UCLA Law since day one, along with a nimbleness that has allowed the school to enhance

its founding mission of public service by repeatedly adapting to a changing world.

“The fact that we’re among the youngest major law schools in the country means that we have the freedom to build new ways of training lawyers, learning lessons from what has come before,” said Cara Horowitz ’01, executive director of the Emmett Institute.

A legacy of leadership

At a time when environmental regulations are under threat, Emmett Institute students work to protect vulnerable communities from pollution. Meanwhile, researchers are delving into the legal underpinnings of energy policy, geoengineering, and environmental governance in China, to name a few initiatives.

“California has been at the forefront of environmental protection and climate change innovation forever,” Horowitz said. “This makes the institute an important place to think creatively about what communities should be doing to advance environmental protections. There are opportunities to push the envelope in California that I don’t think exist elsewhere.”

This perspective carries throughout UCLA Law's programs, centers, and institutes.

The Lowell Milken Institute for Business Law and Policy, the longtime home of UCLA Law’s nationally renowned business and tax law faculty, regularly hosts summits where practicing lawyers come together to share insights on key matters in business law. It also sponsors the annual Lowell Milken Institute–Sandler Prize for New Entrepreneurs competition, providing a significant boost to students with actionable business plans. Meanwhile, the newer Lowell Milken Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofits delves into the study of one of the most pertinent emerging areas, as baby boomers retire and “the Great Wealth Transfer” continues.

Milken ’73 said that his motivation was “to provide students with a broad range of opportunities beyond just their academic training. I also wanted to provide the faculty with opportunities for greater visibility for their research and work, and to engage the broader community— both legal and nonlegal— in issues where UCLA Law could play a leadership role.”

The Ziffren Institute for Media, Entertainment, Technology and Sports Law is another key hub where scholars and practitioners work with students and outside partners to foster a new generation of lawyers adept at contending with contemporary matters.

This includes work in emerging technology; name, image, and likeness issues in sports; and patents. The institute also helps produce the annual UCLA

Entertainment Symposium, the preeminent summit of entertainment lawyers, now in its 49th year.

Ken Ziffren ’65 founded the institute, which built on the law school’s existing programming and expansive reputation as the nation’s No. 1 school for entertainment law. “The whole idea of it appealed to me,” he said. “The law school, I think, is famous, or notable, for its programs. And my interest was in both giving back and at the same time giving students the opportunity to come into the media and entertainment sector better prepared than if the institute didn’t exist.”

Philanthropic visions have driven other centers to immense success.

The Promise Institute for Human Rights was inaugurated to boost UCLA Law’s changemaking scholarship on an array of issues, from migrant rights to accountability for violations to environmental harms. The Promise Institute Europe, meanwhile, places students on the front lines of global policymaking through semesters spent working and learning in The Hague.

The Resnick Center for Food Law and Policy is a pioneer in global scholarship and advocacy. It partners with the United Nations and other important organizations to create guidelines on food governance. It produces a podcast featuring interviews with leading food law experts. And it takes on issues that are not often addressed in law schools, allowing students to play a leading role in its cutting-edge movement toward improved health and sustainability.

The Center for Immigration Law and Policy has led advocacy for migrants, DACA recipients, and other people involved in the American immigration system, and it has notably ramped up efforts as regulations change seemingly by the day and uncertainty abounds.

The Native Nations Law and Policy Center makes a meaningful mark as a place that promotes ground- breaking scholarship, enables community-driven projects, and builds a pipeline for the most promising advocates and academics in the Indian law space. A significant amount of the center’s work happens on the ground through the Tribal Legal Development Clinic, which engages in quality-of-life and other justice issues.

And the David J. Epstein Program in Public Interest Law and Policy is the home of UCLA Law’s legendary and fundamental work in public interest law. Each year, the program turns out graduates who continue to wage many of the most important fights for fair- ness— the kind of legal work that has characterized the law school since 1949.

As Horowitz said, “California is a state where the politics still allow for innovative solutions to tough problems. This means that our students can work on real-world solutions to tough problems in our own backyard. It’s incredibly motivating and rewarding to see our work make a difference in the world.”

Promoting progress

For most of its first quarter-century, CRS has stood as a signature endeavor of UCLA Law. It was founded in 2000, four years after California voters passed Proposition 209 to prohibit state governmental institutions from considering race, sex, or ethnicity in public education. “Prior to that, UCLA was one of the most diverse law schools in the country, but diversity dropped dramatically as lots of students of color didn’t want to apply, thinking it was not a welcoming environment,” said Jasleen Kohli, the program’s executive director.

CRS was the first effort at any law school to incorporate critical race theory into legal scholarship and teaching. From the start, it has been the home of many of the nation’s leading scholars in critical race theory. The program’s singular mission: to train new generations of legal advocates and scholars who are committed to racial justice. Students who specialize in CRS move on to jobs in local, state, and federal government, as well as public interest work in areas such as environmental justice, workers’ rights, and housing.

“As the years have gone by, our reputation has really grown,” said Kohli, who added that a third of 1L students come to UCLA Law intending to pursue a CRS specialization. “I’ve had students tell me that this is the only law school they applied to because of the Critical Race Studies program. We’ve attracted so many faculty and students who are invested in racial justice and in understanding how to use the law to create real, transformative change.”

Their success serves as a symbol of the impact that the law school’s programs, centers, and institutes create: While the challenges are complex, UCLA Law is now, more than ever, a wellspring of solutions.

UCLA Law is grateful to funders who support our institutes, centers, and programs.

Read more in the 75th Anniversary edition of the UCLA Law magazine.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.

“Gary Schwartz, a mentor, was brilliant and quirky, a voracious reader with a keen legal mind. He profoundly shaped tort doctrine through his scholarship and through his work as a reporter on the first part of the mammoth Restatement (Third) of Torts for the American Law Institute.”

Richard Hasen on Gary Schwartz

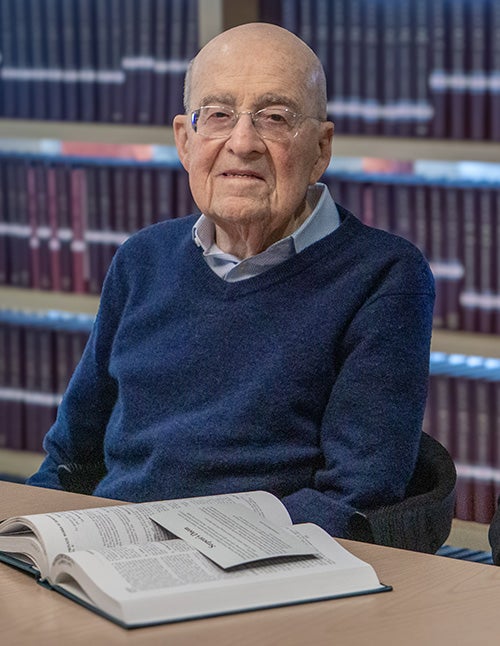

Arthur Greenberg and Joseph Tilem, members of UCLA Law’s very first class, look back on their time in law school and extraordinary careers.

A law school at its start

Tilem, now 98, was a UCLA undergrad when he heard that a law school was opening. He walked across campus and found someone taking the names of those wanting to be considered for admission. “I put my name down and later was pleased to learn I was accepted,” he said.

Greenberg wanted to go to law school at Stanford, where he had spent his undergraduate freshman year before transferring to UCLA, but his parents wanted him to stay close to home. Although his family lived near USC, Greenberg chose UCLA Law.

Watch "A Conversation with UCLA Law's Inaugural Class" and join Dean Michael Waterstone as he sits down with Arthur Greenberg and Joseph Tilem, alumni from UCLA Law's historic first graduating class of 1952. In this conversation, Arthur and Joe both share their memories of early campus life, reflect on their distinguished careers, and discuss how their UCLA Law education shaped their professional journeys.

Both men — two of the last living members of UCLA Law’s very first class — had vivid memories of the school’s early days. “For two years, we had classes in barracks — like the ones I slept in the army — behind Royce Hall,” Greenberg recalled.

Tilem chimed in: “Yeah, there was a room where we could spend spare time, and a few of us would occasionally play cards there, with nickels, dimes, and quarters. But it all came to a halt when Dean Coffman came through, giving a tour to deans from other law schools. We were chastised, and the next day, an edict went out: ‘No card playing.’”

The two remembered the school’s first dean, L. Dale Coffman, as “running a tight ship.” He was “tough, not particularly friendly,” Greenberg said.

In a class of 49 men and five women, the top two students were female. It was, Tilem noted, “the great irony.”

Classes met six days a week at 8 a.m. The men agreed that there was no time for a social life; they were “glued to the books.” They took notes in class “furiously” and typed them up at night. “You’d summarize the lecture into 10 lines on a tissue paper that was gummed on one side, and stick it into a notebook,” Tilem said.

The construction of a building was a major milestone for the new school. Both men remember watching it go up “brick by brick.” When it opened, “it was kind of shocking to walk into it,” Tilem said. “Some of the doors didn’t open properly. There were a lot of little things that still needed work. It had an enormous library, and I got a job there, putting books on the shelves for $1 an hour.”

“Don’t focus too narrowly on one thing, because something is going to come in from left field. It’ll change your life. It did mine.”

Their careers take flight

After graduating, Greenberg joined a firm in down- town Los Angeles at a salary of $400 a month. His partners were specialized, focused only on certain types of cases, so he tried to handle everything else — “whatever walked through the door.”

In questioning prospective jurors for his first case, he knew he wasn’t supposed to ask a woman if she was married. “So I said, ‘Mrs. Smith, is there a Mr. Smith?’ She answered, ‘Yes, there are many.’”

In 1959, he joined attorneys Philip Glusker and Irving Hill in forming Greenberg Glusker above a Safeway store on Wilshire Boulevard. Hill, the most experienced of the three, charged $30 an hour; Glusker and Greenberg, $25. Today, the firm— now in Century City — charges $1,000 an hour.

As for Tilem, in his second year of law school, he was hired as a law clerk at a firm on South Beverly Drive, for 90 cents an hour. “I really just filled the paper machine and cleaned up in the office,” he said. “When I passed the bar, they raised me to a dollar an hour.”

But his fortunes changed when he got a call from one of the firm’s clients, Alfred Bloomingdale, owner of Diner’s Club, which created the world’s first multipurpose credit card. Bloomingdale invited Tilem to work for him for $600 a month. “I felt it might be disloyal to leave the firm with a client, so I called my father for advice. But I couldn’t forgo the salary, and I was at Diner’s Club from 1954 to 1960.”

Then, when Hilton Hotels started a credit card company, Barron Hilton hired Tilem as vice president. In that role, he traveled to South America, Europe, and the Middle East, trying to get banks to accept the Hilton card.

Next, Tilem started his own law firm, which grew to 11 members. He started another new chapter when he was elected mayor of Beverly Hills. He recalled, “Being mayor was like taking a postgraduate college education in dealing with street lighting, union negotiations, what kind of trees you’re allowed to plant in a city, and a whole range of human activities that you would never encounter in any other way except when you’re in the hot seat at city hall.”

Tilem and Greenberg reconnected occasionally over the years. Notably, they crossed paths when Greenberg Glusker handled the savings and loan crisis in L.A., which Greenberg remembered as a “very bitter, tough experience.” Tilem, who at the time was on the board of a failing savings bank, remembers being deposed by Greenberg. “I was scared,” he admitted. “It’s very different when you’re being deposed rather than taking the deposition.”

UCLA Law’s lasting impact

“Arthur and I went in very different directions,” Tilem said, “but the nucleus of our life experience has been based on what we did in law school. Sometimes, years later, a case you had in school applies to what you’re doing.”

He said UCLA Law taught him the importance of working together by partnering him with a classmate to study for the bar exam. “That taught me the need for talking with your colleagues,” he said. “As a result, later in my law practice, I had no problem walking into my partner’s office to discuss a case.”

Asked what advice he’d give to graduating students today, Tilem said: “Keep your options open. So much of it is serendipity. You never can tell when opportunity is going to arise. Don’t focus too narrowly on one thing, because something is going to come in from left field. It’ll change your life. It did mine.”

Greenberg advised: “Be careful in choosing where to practice law. Some firms are better than others in how they treat people. That’s a serious issue. But the law practice to me was exciting, interesting, profitable, and happy.”

Read more in the 75th Anniversary edition of the UCLA Law magazine.

Celebrating 75 Years of UCLA Law

Join the dean of UCLA School of Law, Michael Waterstone, UCLA Chancellor Julio Frenk, and distinguished faculty, students, and alumni as we celebrate 75 years of UCLA Law. This video tribute honors our history of legal innovation and vision for shaping tomorrow's legal landscape. From groundbreaking scholarship to producing leaders who have transformed the practice of law, UCLA Law continues its tradition of excellence while looking boldly toward the future.