UCLA School of Law professor Ingrid Eagly has been selected for the Fulbright-Schuman European Union Affairs Program, which provides opportunities for scholars to conduct research and engage in academic exchanges related to E.U. policies and institutions.

As the November election approaches, UCLA School of Law’s Safeguarding Democracy Project has teamed with the Hammer Museum at UCLA to host a series of public forums that address some of voters’ biggest concerns, such as the fairness of the electoral college, allegations of election fraud and the spread of misinformation.

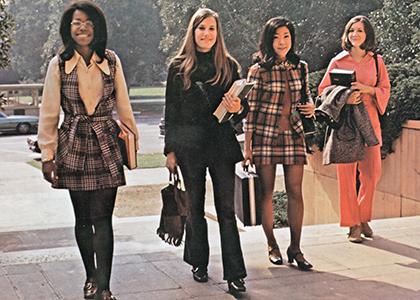

People from across the UCLA School of Law community are proud to be marking the law school’s 75th anniversary during the 2024-25 school year. For 12 months, a series of events, publications, projects and programs will bring together friends and colleagues to reflect on their rich history of public service, access to justice, and outstanding legal education.

The celebration is rooted in an ethos that has driven the law school from the beginning.

“UCLA Law has played an important role on the local, national, and international stage.”

Today, Dean Michael Waterstone looks at that dynamic period and sees how it formed the enduring mindset of advocacy, invention and unity that characterizes the law school.

“UCLA Law was united by commitments that we continue to hold today: a determination to care for our neighbors, engage in a cutting-edge education, and achieve excellence while creating a more open and equitable legal profession,” Waterstone wrote in a message that kicked off the anniversary celebration. “UCLA Law has played an important role on the local, national, and international stage. Our faculty members have been at the forefront of every key legal and policy debate during that period, serving as thought leaders and changemakers. Our alumni have held key positions in law, business, politics, and civil society, bringing our values into action around the world. And every day, our students have shown up, committed to bettering themselves and making a meaningful difference in their communities.”

“This anniversary is a moment to reflect on everything that makes us great and the even better opportunities that are on the horizon.”

Anniversary programming starts with a special law school tailgate at the UCLA football game on September 28 and Reunion 2024 weekend on October 19 and 20. More events in the spring will include a block party for the entire UCLA Law community and the Alumni of the Year awards ceremony (details on these activities are to come).

A special 75th anniversary website features details on anniversary events and much more. It will be updated throughout the year and allows readers to be inspired by stories from the past three-quarters of a century and focus on the values that guide UCLA Law.

“This anniversary is a moment to reflect on everything that makes us great and the even better opportunities that are on the horizon,” Waterstone said to the community. “Thank you! I’m thrilled to be on this journey with you.”

When Ralph Shapiro died earlier this month, we lost a great alumnus and dear friend. Along with his wife Shirley Shapiro, Ralph has been a longtime supporter and champion of the UCLA School of Law and the Emmett Institute on Climate Change & the Environment.

When Ralph Shapiro died on August 14, UCLA School of Law lost one of its most distinguished alumni and best friends. Shapiro was a Double Bruin who received his bachelor’s degree from UCLA in 1953 and graduated from the law school in 1958, and he enjoyed a remarkable career as a lawyer, businessman, philanthropist, and eminent supporter of his alma mater.

“In our community of many great leaders, Ralph was a titan.”

Ralph J. Shapiro, a UCLA alumnus, renowned business leader, philanthropist and enthusiastic, lifelong supporter of the university, died Aug. 14 at the age of 92. He was a proud Bruin and for more than half a century played an immense role in the life of the campus as a donor, volunteer, mentor, advisor, board member and friend.

Shapiro’s family immigrated to the United States from Lithuania when he was a boy and settled in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights. He earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from UCLA in 1953 and a juris doctorate from UCLA School of Law in 1958. UCLA was also where Shapiro met his wife, Shirley, an alumna of the class of 1959 who received her bachelor’s in education.

Throughout his life, Shapiro credited UCLA with providing him and so many others with the opportunity of a world-class public education. He was thankful to the university and dedicated to investing in its faculty and students to enable them to do great things for the betterment of the world. He and Shirley gave generously to a broad range of campus areas, including athletics, the arts, law, music, dentistry, nursing and more.

“UCLA has lost one of its great champions with Ralph’s passing. His contributions to our campus are almost incalculable — he had a great vision for what UCLA could be and dedicated himself to helping the university realize its highest aspirations,” said former UCLA Chancellor Gene Block. “Over many decades, Ralph and Shirley made gifts to more than 100 departments and touched the lives of countless individuals in ways that were profound, inspiring and impactful. Our deep gratitude and our heartfelt sympathies are with his family, friends and loved ones.”

Across six decades of support and leadership, the Shapiros displayed their profound commitment to the Bruin community, giving more than 1,600 gifts — twice as many as any other family at UCLA — to virtually every corner of campus. They endowed more than 20 faculty chairs in areas including piano performance, pediatrics, the study of developmental disabilities and other specialties in health sciences and law, and created the Shirley and Ralph Shapiro Directorship at the Fowler Museum. Grateful for the scholarship support that enabled him to attend UCLA — which he credited with changing his life — Shapiro remained a firm believer in the power of student support. Over the years, he and Shirley provided scholarship aid to more than 700 students. In addition, he was a loyal fan of Bruin athletics and held basketball and football season tickets for more than 30 years.

A tireless advocate for the university, Shapiro took great pride in motivating others to support UCLA’s highest-priority needs. Over the years, he served on 30 UCLA boards and committees, including the cabinets for Campaign UCLA and the Centennial Campaign, the medical sciences executive board at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and The UCLA Foundation. He was president of UCLA School of Law’s alumni association from 1965–66 and a member of its board of advisors for decades. In 1983, he received the school’s Alumnus of the Year award.

In recognition of his commitment to UCLA’s success and impact, Shapiro was named the university’s Alumnus of the Year for Public and Community Service in 2008. And in 2019, along with Shirley, he received the university’s highest honor, the UCLA Medal, which recognizes contributions to society that illustrate the highest ideals of UCLA. The Shapiro Fountain on Royce quad and the Shapiro Courtyard adjacent to the law school were both named in recognition of the couple’s prolific giving.

“As generous as Ralph was with his financial support of UCLA, he was equally giving of his time and counsel,” said Rhea Turteltaub, UCLA’s vice chancellor for external affairs. “He and Shirley cherished every opportunity for meaningful involvement in the life of the university, lending their energy over the years to dozens of boards and committees. Ralph was a fierce advocate for UCLA, time and again providing sage advice and trusting in leadership to make the most effective use of his philanthropic support as together we shaped the future of the university. He played an outsized role in making us the flourishing institution we are today.”

Recognized as a leading investor in commercial real estate in Southern California, as well as in diversified securities, Shapiro served as chairman of the Avondale Investment Co. Early in his professional life, he practiced corporate and real estate law in Beverly Hills, helping major corporations settle complex disputes.

Shapiro’s generosity extended beyond UCLA as well. His passion for philanthropy led to the establishment of the Shapiro Family Charitable Foundation in support of a range of interests, including the environment, arts, health and education. A particular focus of his attention was support for families affected by cerebral palsy. He and Shirley invested their hearts in this cause, personally giving their time and care to parents and children alike.

Acknowledging Shapiro’s incomparable contributions and lasting impact, UCLA Interim Chancellor Darnell Hunt said, “Ralph Shapiro led a truly extraordinary life. Through his passion, hard work and talent, he scaled great heights, and through it all, he kept UCLA near and dear — never missing an opportunity to make our university a better place to learn, to teach, to work or to carry out research. Across the span of a life dedicated to higher education and service, Ralph Shapiro never forgot his alma mater, and the Bruin family will never forget him.”

Shapiro is survived by Shirley and his children, who share his devotion to public service and the greater good.

Gifts in Shapiro’s memory can be made to the Shapiro Luskin School Special Patient Care Fund.

As UCLA School of Law kicks off its 75th year, a cohort of remarkably accomplished students has joined the law school’s community and is poised to make an impact from the start.

The incoming students include 317 who are pursuing a juris doctor degree (J.D.) as members of the Class of 2027, 220 who are working toward a master of laws degree (LL.M.), and 89 who are earning a master of legal studies degree (M.L.S.).

“This is a big moment in your lives. You are about to embark on an incredible adventure.”

Under sunny and comfortably warm skies, UCLA Law officially welcomed the new students at its annual convocation ceremony, on UCLA’s Dickson Court, on August 23. Speakers included UCLA Law dean Michael Waterstone, Student Bar Association president Scott La Rochelle ’25, and Judge Philip Gutierrez ’84 of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California.

“You are now members of our community, and we know you will continue to make us better. This is a big moment in your lives. You are about to embark on an incredible adventure,” Waterstone said. “You will figure out how to craft innovative and joyous ways to make a positive impact in the legal profession, your communities, and the world.”

He went on to emphasize that, at UCLA Law, the students will gather skills to help them tackle problems in a society where traits including compassion and reflection seem to be in dwindling supply. “Being a great lawyer means that you have to be able to understand someone else’s point of view – whether it’s your client, a colleague, opposing counsel, or a judge. And you must articulate your own perspective with calm, with clarity, and even with kindness.”

“Empathy starts really with one thing, and that’s listening.”

Gutierrez, a law school alumnus and federal judge, administered the Oath of Professionalism and elaborated on the same theme – the importance of developing relationships, maintaining strong ethical behavior, and practicing empathy as a path to success in the law and life.

“Empathy starts really with one thing, and that’s listening,” he said. “You can’t have empathy for somebody else unless you really listen to what that person has said about what they’re going through, how they’re feeling, or what their opinions are.”

The entering J.D. class is 54% women and 62% who identify as students of color. In addition, 18% of the class members are the first in their families to earn a four-year college degree.

Among their many impressive records of accomplishment and service, incoming J.D. students include one Fulbright Award recipient, nine high school valedictorians, and eight people who graduated from UCLA Law’s Law Fellows Program. Four have already earned Ph.D.s, and 26 hold master’s degrees. Many come to law school after having worked at leading companies, law firms, and government offices, including the White House; U.S. Senate and House of Representatives; U.S. Departments of State, Justice, Defense, and Veterans Affairs; FDIC; CIA; and FBI. With many star athletes, artists, businesspeople, published writers, scientists, and teachers, the class includes speakers of at least 28 languages.

New students also come with a longstanding commitment to public service. They have volunteered or worked for Asian Americans Advancing Justice, the Center for American Progress, the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, the Council on American-Islamic Relations, the International Rescue Committee, Kids in Need of Defense, the NAACP, the National Women’s Law Center, and the Peace Corps, as well as a wide array of other organizations that advocate for and protect the rights of people around the country and world. (Read more about this impressive group on the J.D. class profile.)

Several other people who are working toward a J.D. degree have earned a warm welcome to the law school community this year. These include 35 students who came onboard as members of the Class of 2026, now beginning its second year, and six visiting students who will complete their legal education at UCLA Law.

Already lawyers in various areas of practice and work, the new LL.M. students come from 41 countries, having earned their law degrees from leading schools on six continents. A full 60% of the class is made up of female students.

The cohort includes people who have worked at major global law firms and corporations, as well as two Fulbright scholars and people who have served in the Supreme Court of Japan, the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Finance, the Constitutional Court of Korea, the Italian Interior Ministry, the New York Department of Financial Services, and the U.S. Small Business Administration. There are prosecutors from Japan and Korea; judges from Germany, Japan, and Korea; and clerks for the Supreme Court of India and the Higher Regional Court of Vienna. Two students are Health and Human Rights Fellows from Ghana and Russia, and two others, from Ireland and the United States, are Critical Race Studies Fellows.

The law school also welcomed two S.J.D. students: one, from Chile, recently earned an LL.M. degree at UCLA Law and will embark on a project researching the effects of regenerative farming practices on environmental and human outcomes; another, from Nigeria, will conduct a comparative analysis of campaign finance laws in the United States, Canada, and Nigeria. In addition, 11 foreign exchange students join the law school community from partner schools in Austria, China, France, Germany, Israel, and Spain.

Members of the M.L.S. class are accomplished professionals who are attending UCLA Law to earn a degree that allows them to master legal principles and advance their careers but does not qualify them to practice law. This year marks the launch of the program’s online or hybrid model of education, and 45 incoming students are pursuing their degrees online, while 44 have chosen the hybrid option.

For the full incoming M.L.S. class, 71% of the students identify as female, 69% identify as students of color, and their average age is 35. As accomplished professionals and leaders in their fields, 46% are chief executives or vice presidents, 14% are directors or managers, and 43% hold advanced degrees. They work at the highest levels of journalism, nonprofits, business, city government, medicine, community affairs, and emerging technology.

-

J.D Environmental Law

-

J.D. Business Law & Policy

-

J.D. Critical Race Studies

-

J.D. David J. Epstein Program in Public Interest Law & Policy

-

J.D. International and Comparative Law

-

J.D. Law and Philosophy

-

J.D. Media, Entertainment and Technology Law & Policy

-

LL.M. Program

-

Master of Legal Studies

-

S.J.D Program

UCLA School of Law Professor Emeritus Gary Blasi is among the winners of UCLA’s 2024 Public Impact Research Awards.

Tapping into her career-long commitment to public service and student mentorship, Erin Han has joined the Judge Rand Schrader Pro Bono Program at UCLA School of Law as its director.

-

J.D. David J. Epstein Program in Public Interest Law & Policy

Michael Dorff, a dynamic leader in legal education and authority in corporate law, has joined UCLA School of Law as the executive director of the Lowell Milken Institute for Business Law and Policy.

With deep expertise in the law of prisoners’ rights, UCLA School of Law assistant professor Aaron Littman is poised to engage in further cutting-edge research with the support of a prestigious fellowship that goes to the most promising pre-tenure faculty members across all fields of study, throughout University of California system.